In this instalment of the ‘Calf Health Series’ – brought to you by AgriLand and Volac – we will examine the area of calf housing and why adequate conditions are so important in terms of calf health and overall animal performance.

Providing the correct housing environment is central for a calf to reach its genetic potential and to avoid stress and health issues. Inadequate housing can be linked to increased incidents of respiratory disease and scours.

The calf shed should be properly ventilated, in a stand-alone building, located upwind of other cattle housing facilities and at right angles to the prevailing wind.

Calf pens should be free from draughts and have ample lighting. It is essential to avoid under-draughts at calf level, while optimum calf conditions occur at temperatures of 10-20ºC – with humidity at 65-75%.

In addition, these pens should be constructed with durable and easy to clean material.

Houses should, where possible, be thoroughly cleaned, disinfected and left for three-to-four weeks after each batch of calves to dry out and allow reservoirs of bacteria to die out.

Moreover, housing facilities should have convenient access and storage for feed, bedding and water supplies.

Ventilation in the calf house

Fresh air is often one of the scarcest things in a calf house. Moisture produced from feed, urine and respiration, if not removed by ventilation, creates damp and humid conditions in which certain bacteria and viruses can thrive.

When a calf’s coat gets damp and loses its insulative value, the young calf cannot maintain thermal equilibrium and can literally be chilled to death at temperatures well above freezing.

Damp calves will use more energy to keep warm and have less available for growth, so performance will suffer.

If, on the other hand, humid conditions in the calf house are controlled and the calf’s coat remains dry, the calf can be comfortable at temperatures well below freezing.

Besides upsetting the calf’s natural insulation, high relative humidity is the ideal environment for disease pathogens (respiratory) to live and multiply.

A well-ventilated house removes moisture generated by the animals without creating a draught. On still days, the heat produced in the building by calves warms the air.

The warm air rises and leaves the building via an adequately-wide outlet ridge, if it’s wide enough, and the stale air is replaced by cooler, fresher air entering above the calf’s height at eaves level.

Ventilation should remove moisture vapour products, disease organisms, dust and foul air, and replace this with fresh air.

Ventilation should also remove by-products such as ammonia, hydrogen sulphide, carbon dioxide and methane. High levels of this can increase the calf’s susceptibility to disease.

As a rule of thumb, if you can detect smells in the calf house, there is not adequate air movement inside the unit. However, draughts need to be avoided and micro-environments work well to prevent this issue.

Calf bedding and drainage

Calves spend 80% of their time lying down. Therefore, the quality of bedding material used is extremely important, as it is crucial to reduce the amount of heat lost via conduction from lying calves.

Deep straw bedding is superior to other bedding material in its efficacy as an insulator. It can help prevent against calf respiratory disease in naturally-ventilated sheds.

Straw bedding should be at least 15cm deep and should remain dry at all times. Wood shavings and bark chips can also be used to provide the calves with dry lying conditions.

Calves require up to 20kg/head/week of straw bedding in order to maintain dry conditions on concrete floors.

This quantity can be halved by using slats under the straw. For routine bedding, generously top up the existing bed with straw. The bedding should at all times be dry enough to allow you to kneel in the pen without your knees getting wet.

This ensures that the calves have a comfortable and dry lying environment at all times that will minimise the spread of disease.

When selecting bedding materials it is important to avoid using dusty bedding, as it can cause respiratory problems.

In terms of drainage, a 1:20 slope is necessary to remove any excess water under the calves, with a drainage point available at the exit of the calf area to take excess liquids away.

Falls should be designed so that excess liquid does not mix from pen to pen. Additionally, water, milk and concentrate feeding stations should be located at the draining point – minimising wet-soiled areas, as calves will excrete more at these points.

Space requirements and outdoor access

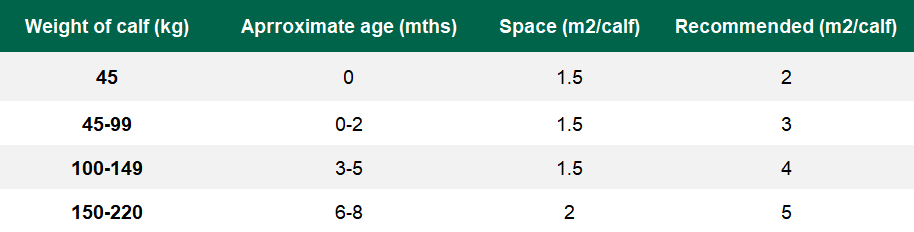

In terms of stocking density, overcrowding should be avoided to allow ample air space.

Generally speaking, there should be 1.1m² of space for calves aged four weeks. This should increase to 1.8m² for 12-week-old calves and 7m³ of air capacity/calf is recommended.

The ideal group size is 12-15 calves/group, with a maximum of 20 calves/group advised. It is also important to keep the age range to a minimum; seven days is ideal with 21 days-of-age being the maximum.

Furthermore, providing access to an outdoor pad – with a dry lying area – is an excellent addition to the calf-rearing environment.

Disease risks are lowered substantially, as calves tend to spend quite an amount of time lying outside irrespective of temperature.

Dealing with cold conditions

With cold weather, the challenge for all calf rearers is to keep calves healthy and optimise growth rates.

Calves should be fed a higher plane of nutrition when temperatures begin to drop in order to consistently achieve growth rates even under cold stress.

When temperature falls, calf growth rates can plummet, simply because calves require so much more energy just to keep warm and there is, therefore, less available energy for growth.

Less energy is also available for immune function, so calves are more susceptible to respiratory infections and scours.

Lower Critical Temperature (LCT) is the temperature at which animals begin to require additional energy to maintain their body temperature. For calves at 0-3 weeks-of-age, the LCT is 20°C; for calves older than 3 weeks-of-age it’s 10°C.

For a young calf (0-3 weeks-of-age) weighing 50kg, as a rule of thumb, feed an extra 100g milk powder/day for each 10ºC drop in ambient temperature below 20ºC, for them to continue to grow at the same rate as when it’s warm outside.

If the outside temperature is 0°C, feed young calves (0-3 weeks) an extra 200g/day.

If you normally feed 625g/day, you will need to feed calves a total of 625g + 200g = 825g/day of calf milk powder for calves to continue to grow at the same rate as when it’s warm outside.

Calf jackets

Calf jackets keep calves warm, dry and healthy in the winter when temperatures fall below 15°C. But remember, calf jackets do not replace good calf husbandry.

These jackets should be used in combination with good management practices such as providing the calves with a draft-free environment and deep, dry bedding – which helps the calf maintain good growth and support strong immune function, reducing the risk of setbacks.

Part 1: Calf Health Series: The power of colostrum must not be underestimated

Part 2: Calf Health Series: What should I feed, and how much, for optimum condition?

Part 3: Calf Health Series: Which feeding system is best suited to your farm?

Part 4: Calf Health Series: Hygiene and biosecurity must not be overlooked in the calf house

More information

Volac has been involved in young animal nutrition for the past 40 years and is an innovator in this field.

The company is committed to helping farmers make the most of their calves and has developed a range of specialised milk replacers, which are specifically formulated for modern dairy and beef animals.

For more information, contact a Volac representative today, or visit the Volac website by clicking here