In Part 1 of the ‘Calf Health Series’ – a joint initiative brought to you by Volac and AgriLand – we will discuss the when and how much of colostrum, a calf’s fuel for life, and why it is so important that a calf receives an adequate amount in the early hours of life.

Despite all the literature regarding the importance of colostrum, many farmers fail to ensure calves have received sufficient quantity and quality. Failure of passive transfer (FPT) remains a common phenomenon globally – not just on Irish dairy farms.

It is essential that the calf consumes an adequate amount of high-quality colostrum in order to achieve immediate protection, until they begin to produce antibodies after about four weeks-of-age.

Calves that do not receive enough antibodies through colostrum – soon after birth – are more susceptible to illness, and are at an increased risk of developing diseases, which can result in ill-thrift, reduced performance or even mortality.

When it comes to feeding colostrum, there are a number of factors that need to be considered, including: quantity, quality, quickly and cleanliness.

Firstly, a calf should be fed 10% of its body weight (normally 3-4L). This colostrum should be collected at the first milking (ideally collected within two-to-six hours after calving).

Once collected, the calf should receive the above amount within the first two hours of life (six hours maximum), whilst the gut wall is permeable and antibodies can pass directly into the bloodstream.

Farmers can ensure sufficient intakes by bottle feeding or stomach tubing colostrum; veterinary advice should be sought for the correct use of a stomach tube, as oesophageal bruising can easily occur due to inappropriate use of this equipment.

This is important as a calf left to suckle the cow may not consume enough colostrum within the critical early period or poor teat conformation can reduce a calf’s ability to drink correctly.

In light of this, it is best practice to remove the calf from the cow as soon as possible to avoid the risk of disease transfer from cow-to-calf; a cow’s dirty udder can also be a source of infection to the calf.

Cleanliness is vital when harvesting colostrum and preparation of the cow’s udder, disinfected equipment and correct storage techniques are critical in order to prevent bacterial contamination in colostrum.

While feeding the correct amount of colostrum at the appropriate time is crucial, there is no point storing or feeding poor-quality colostrum.

Many cows within a herd will produce poor-quality colostrum. Traditionally, colostrum from heifers has been discarded. However, with well-managed feeding and vaccination programmes, heifers are now capable of producing good-quality colostrum – so check the quality first.

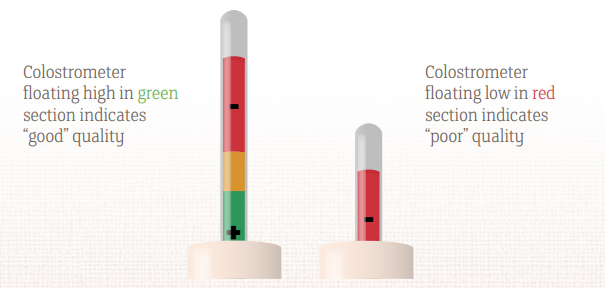

But, saying that, it’s no good just looking at colostrum – even if it looks thick and creamy it may be sub-standard; a colostrometer will give you a quick, simple assessment of its quality.

A simple colostrometer will estimate the quality of colostrum – it should have a minimum of 50-60g IgG/L. Refractometers can also be used to assess colostrum quality, with a Brix score of 22% (50mg/ml) proposed as the cut-off for identifying good-quality colostrum.

When using a colostrometer, place the test sample of colostrum in a clean cylinder, allowing it to cool to room temperature (20-22°C) for accuracy. If it is too warm, the colostrometer may underestimate the antibody quality.

Additionally, in an ideal world, froth should be kept to a minimum; too much will make the scale hard to read.

Reading the results is straight forward. If it floats in the green section, the quality is good; this should be fed to the newborn calf as soon as possible (ideally within 2 hours), or it can be stored.

If the colostrometer floats in the orange section, the quality is average; this should not be fed to the newborn calf (during the first 24 hours), but it is fine for two-to-three day old calves, which have already consumed good-quality colostrum.

However, if the colostrometer floats in the red section, the quality is poor and should be discarded or fed to older animals. Good-quality colostrum can be stored in the fridge for up to seven days and in the freezer for up to one year.

However, bacteria will still grow in the fridge, so it should be used within two days or frozen within one-to-two hours of collection; but, if it is left at room temperature, bacteria will double every 20-30 minutes.

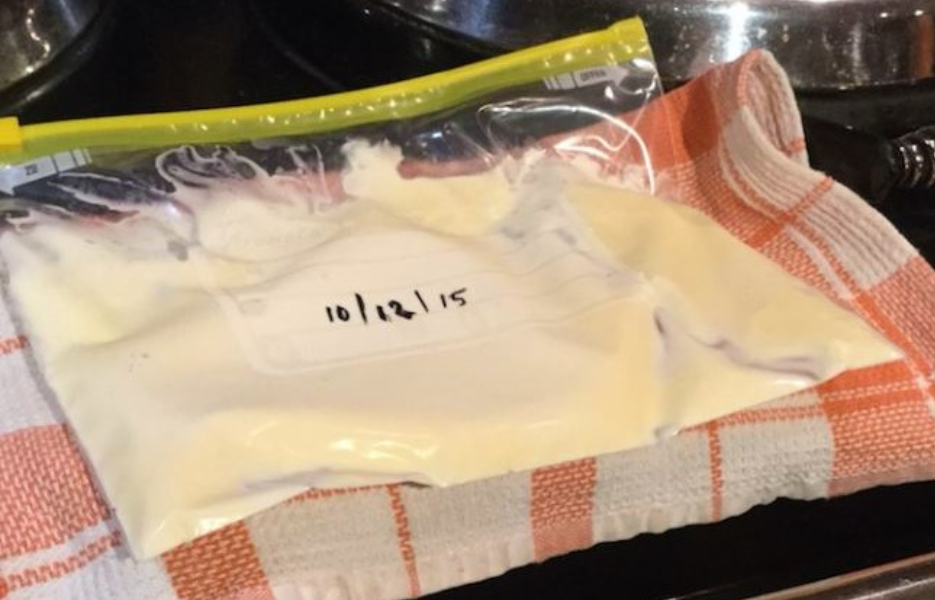

Colostrum should be stored in 1L zipper packs to allow effective freezing at -18°C to -25°C; the 1L pack will also aid thawing; this should be carried out by defrosting gently in warm water. Microwaving or boiling is not advisable as high heat can damage proteins.

Along with focusing on the quality of colostrum, it’s also important to remember the potential risk of Johne’s disease.

The bacteria that cause Johne’s disease – Mycobacterium paratuberculosis (MAP) – can be present in colostrum, milk and faeces. Colostrum contaminated by MAP is a major risk factor for calves becoming infected with Johnes.

Proper colostrum management is critical in order to prevent the spread of Johne’s disease within a herd; colostrum should be fed from the calf’s own dam (if Johne’s negative).

In the absence of their own dam’s colostrum, or if the dam has been identified as Johne’s positive, only feed colostrum from a single animal that is Johne’s negative.

Additionally, colostrum should not be pooled. By doing so, colostrum allows infection to be spread from one cow to a number of calves; colostrum from neighbouring farms should also be avoided to reduce the spread of disease.

Volostrum

Situations will arise when access to clean, high-quality maternal colostrum is not available for a number of reasons. These may include: poor-quality or no colostrum available from the maternal dam, the cow is Johne’s positive or when there is no frozen or stored colostrum on the farm.

Regardless of the situation, the new-born calf must receive some form of colostrum within hours of being born.

In these cases, a quality colostrum supplement can provide an alternative. Colostrum supplements are a good way of providing biosecurity on the farm when there is a concern over spreading disease or using colostrum from a different farm.

Volac Volostrum is a high-quality, natural alternative to colostrum and is recommended for use when an adequate supply of good-quality, maternal colostrum is unavailable.

Add all the contents to 0.5L (one pint) of warm water (40°C) in a clean bucket. Mix thoroughly with a whisk until smooth. Mix in an additional 0.5L of warm water, making a total of 1.6L (approx three pints).

After reconstitution, Volostrum should preferably be fed to calves via a bucket or bottle and teat, although it may be fed via a stomach tube by experienced personnel.

Volostrum contains a consistently high level of protein and energy. Volostrum provides 450g of nutrients in one feed, giving the calf the energy and protein it needs for a good start in life; it has been successfully tried and tested by farmers for over 20 years.

Focusing on colostrum management on farm cannot be emphasised enough, there is no point spending money vaccinating cows – to boost colostrum with antibodies to the scour causing pathogens, such as E.coli,

K99/Rotavirus/Coronavirus etc. – if this boosted colostrum is not utilised.

Nor is it economically viable watching veterinary costs soar when trying to treat sick calves – it’s the age old theory of prevention being better and cheaper than cure.

Colostrum must be treated as the calf’s most important meal, not only for its immediate immune system benefits, but for its long term role in future milk production; it’s also free.

More information

For more information, contact a Volac representative today, or visit the Volac website by clicking here