Job creation and industrial development is not just about the multinationals.

The very recent and very worrying trend of lay offs in the high-tech sector has led to a government announcement of a reassessment of Ireland’s current industrial development policy.

However when you dive a little deeper into what this actually means, it seems it will involve, not a root and branch exam of industrial policy across the Irish economy, but some tweaking of the incentives for foreign direct investment (FDI).

This narrow view that industrial development regards multinationals only, is daft.

FDI by multinationals

Yes, FDI supports more than 200,000 jobs and has provided our economy with a huge boon in Corporation Tax, but given total employment of 2.5 million and total tax take in 2022 of an estimated €70 billion, it is clearly not the only show in town.

Most importantly, a deeper knowledge of the development opportunities and incentives required for investment in all of the business sectors across the Irish economy, does not exclude the FDI sector.

What is it about the public narrative in Ireland that creates a binary framework around public policy?

Supporting the indigenous sector does not mean excluding support for FDI and vice versa; in the same way that supporting the transformation and decarbonisation of the agricultural sector does not mean ignoring environmental impacts.

Lest anybody forget, the Irish agri-food sector supports over 230,000 jobs directly and indirectly and shows up every year as the biggest source of Irish economy expenditure in the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment’s annual survey.

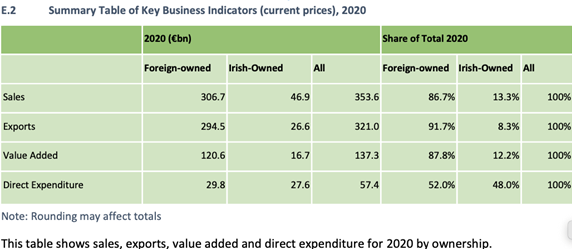

As the chart below shows, it is direct expenditure in the Irish economy that best represents Irish economy impact and the agri-food sector spends four times more than any of the individual FDI sectors.

To repeat again, the major takeaway from analysis of the collapse of the Irish and global economies from 2008 to 2012 was not just the need for greater oversight of financial markets, but above all, the requirement to have a spread of economic activity across the economy.

Support for business

Opportunities for job creation require patient capital and better state aid supports.

Fortunately, in particular since the Covid-19 pandemic, the disposition of the European Commission to allowing governments to intervene to support jobs or economic transition has changed.

From 2005 to 2020, the EU view was overwhelmingly based on an ideology that in an efficient, free, market such as the EU single market, individual government supports for industry would crowd out private capital and would be inherently inefficient and wasteful.

The reality, particularly after the financial crash of 2008, was that private capital disappeared and crowding out was not an issue.

However, it is clear from discussions with our EU partners and the commission that even though Ireland’s low Corporation Tax regime is not covered by EU state aid rules, it is seen in Brussels as a huge incentive for inward investment.

According to Eurostat, the value of the incentive is €160 billion annually, which is the difference between Ireland’s gross domestic product (GDP) figure, which includes multinational profits, and its net national product (NNP) figure, which does not.

So, it is not just Irish economic commentators who fixate on our FDI story.

Challenges

Having said that, it is up to the Irish government across a number of departments to articulate the reality, which is as follows:

- The Irish economy is multifaceted and in particular has an agri-food sector that has unique rural and regional economic impacts;

- The Irish agri sector, uniquely in the EU, has shown over the last 20 years a tremendous capability to adapt and expand;

- The Irish agri sector managed the transition of the EU support system through the abolition of the EU export refund, the dismantlement of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) supports and internal subsidies as well as the challenges of Brexit and Covid-19;

- The Irish agri-sector navigated the Food Vision 2030 process, and in response to global customer demand, is currently/actively responding to the challenge of decarbonisation of the sector.

An assessment of current strategic challenges facing the Irish agri-food sector highlights the urgent need for investment in innovation, product and market diversification in response to Brexit.

It also highlights the creation of new scaled infrastructure that will enable the transition of the agri supply sector specifically, to becoming a scaled up provider of renewable energy through investment in anaerobic digestion (AD) and supply infrastructure.

All of these ‘opportunities’ have the characteristic that they are expensive and require patient capital and also that they are capable of creating significant numbers of jobs across the rural and regional Irish economy.

The reality of economic and industrial policy is that balance must be a guiding factor.

The overwhelming debate in Ireland and across the global economy has been about the achievement of a better balance between economic impact / job creation and environmental impacts.

It is very important that the positive role of the agri-food sector with regard to both of these challenges, and in particular with regard to its ability to support jobs and new economic activity, is properly recognised and prioritised.