The Joint Oireachtas Committee on Agriculture, Food and the Marine is set to write to the finance minister to request that the rules around the percentage of farmland that can be used for solar panels be amended.

The committee convened this week to discuss solar energy in the agricultural sector, where representatives from Teagasc and Irish Solar Energy Association (ISEA) discussed the options available to farmers and the agricultural sector in order to help meet their future carbon emission reduction targets.

The committee discussed the issue of agricultural relief and the impact that the 50% land threshold is having on farmers getting involved in solar farming.

Agricultural relief, under capital acquisitions tax (CAT) rules, allows farming families to inherit agricultural land without being subjected to potentially unaffordable levels of inheritance tax.

But current rules only allow farms with solar panels to qualify for the relief, provided that the panels do not take up more than 50% of the total land area.

The committee, based on a proposal by Green Party TD, Brian Leddin, will write to Minister for Finance, Paschal Donohoe, requesting that all farmland – irrespective of the percentage of land under solar panels – would qualify for agricultural relief.

The ISEA has previously requested that the area be increased from 50% to 80% but the representatives attending the recent committee meeting said they supported the proposal for any limit to be lifted.

Chair of the committee, Deputy Jackie Cahill, said:

“I don’t see why there should be a limit, the whole farm should qualify. It is not as though the farm is gone industrial, it is providing energy, so I would be looking for full agricultural relief for the land, for 100%.”

To this, chief executive of the ISEA, Conall Bolger, responded:

“You’ll get no opposition from us.”

Responding to a question on this issue from Sinn Féin’s Deputy Martin Browne, the chief executive said it was a “material” issue that is “dissuading farmers from participating” in solar farming.

His colleague, Dr. Tara Reale, said that the threshold, which was initially implemented in 2017, saw Ireland follow a trend that was evident in the UK and Northern Ireland, where the tendency was to develop small, community-sized, solar farms with a 4-5MW peak.

Such solar farms, she said, probably only needed 25, 30, to 40ac of land, maximum.

“If we now look at how policy has changed, and to get grid access, you have to go large-scale and, economics-wise, the more you buy the cheaper per megawatt (MW) the actual cost is. That has driven developers towards these very large-scale solar farms,” she said.

This means more land is required.

“Taking into account all the other planning considerations such as visual impact, special areas of conservation, heritage issues, you are limited in where you could, conceivably, put a solar farm,” Dr. Reale added.

Many landowners and farmers are interested in solar farming, she said, for various reasons such as diversification of income, wanting to retire, not having children who want to farm.

But if sufficient land is not available, then the economics simply won’t work, and the project is unviable.

“We have had to turn away a number of opportunities where people were really eager to get into solar but we couldn’t make the economics work.”

Mr. Bolger stated that it was his understanding that the agricultural relief rules are there there to support the retention of land in agricultural use.

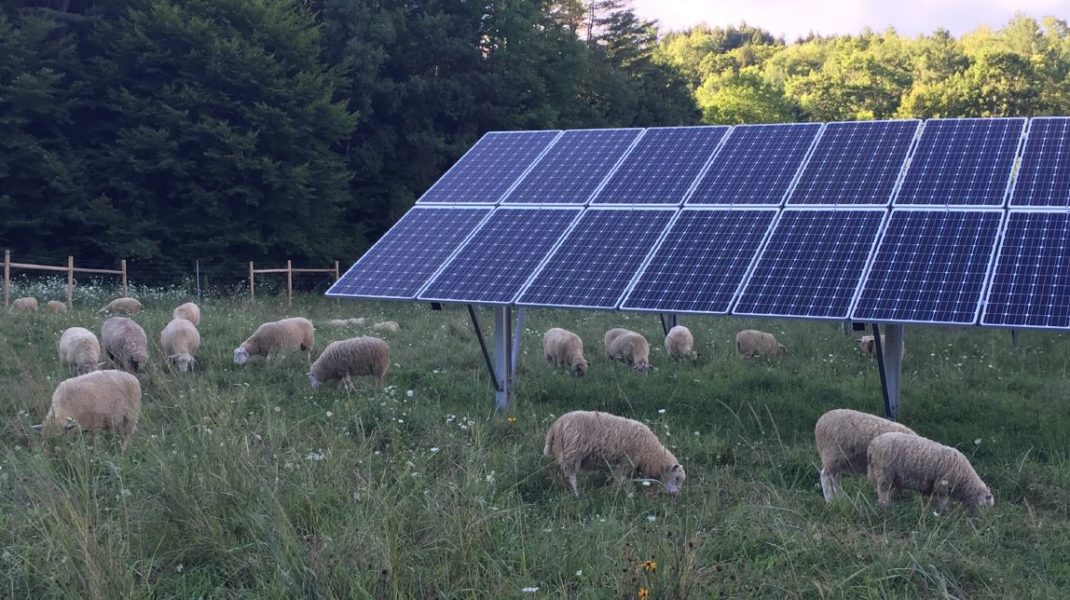

“We would argue that the mixed use of land with solar and other functions – agro-voltaics – such as growing food among solar panels and letting animals graze does meet the definition of farming and agriculture,” he said.