The transition period – the three weeks pre- and post-calving – is full of challenges for the dairy cow. We expect her to go through the physical trial of late pregnancy and calving without suffering any metabolic disorders, as well as going on to achieve peak milk production within 4-8 weeks of calving, with optimal milk solids yield.

On top of that, she needs to show strong signs of heat and get back in calf by day 83 in-milk, to maintain a 365-day calving interval.

This is a lot to ask and requires her to be supported, both nutritionally and through careful management, during this period.

Transition period nutrition

From a nutrition point of view, the demand for major nutrients increases dramatically from approximately three weeks pre-calving to four days post-calving. Demand for fatty acids increases five-fold, calcium demand increases four-fold, glucose three-fold and amino acids two-fold.

This draw on nutrients is controlled primarily by a significant increase in growth hormone levels, which directs energy (glucose) towards the udder for milk production at the expense of the cow’s own body reserves.

This process is facilitated by receptors in the liver becoming insulin-resistant and the uncoupling of the growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor axis, which typically directs nutrients towards the reproductive tract.

If this uncoupling lasts for a long period of time in early lactation, due to a lack of energy, then it can have detrimental effects on fertility three to four months after calving.

It is normal to have a period of negative energy balance in the first few weeks of lactation as the cow utilises her own reserves for maintenance and milk production. It is vital, however, that we manage the transition cow’s diet to close this energy gap as fast as possible to avoid issues with metabolic disorders and resulting poor fertility.

The key thing is to maximise dry matter intake (DMI) during this period by feeding an energy-dense, balanced diet and managing feed access. A glucogenic-based diet to maximise milk yields, minimise body condition loss and facilitate a good immune response; this will also get cows showing strong heat after calving.

It is also critical to supplement with the correct balance of trace elements, antioxidants and minerals.

Risk of metabolic disorders

If transition cows are not managed correctly, several metabolic disorders can occur, leading to poor production and reproductive performance.

What’s more, a cow with one metabolic disorder is more likely to suffer from another problem (e.g. a case of clinical milk fever increases the risk of mastitis eight-fold).

The ability of the immune system to mount a challenge is also lowered during the transition period, making the cow more susceptible to pathogenic diseases like mastitis and metritis. The major risks, however, come from clinical and subclinical ketosis (due to excessive or prolonged energy deficit) along with immune suppression, which can have long lasting effects into lactation.

A suppressed immune system means that there is a higher chance of infection, promoting metabolic disorders and reducing DMI.

Indeed, subclinical ketosis (>1.2mM BHB/L of blood) is negatively correlated with a host of metabolic disorders, with cows 5.38x more likely to get clinical ketosis, 3.33x more likely to suffer a displaced abomasum and twice as likely to suffer lameness.

There are also indirect and direct milk yield losses of around 340kg over the lactation, plus a negative impact on reproduction. We really don’t want a cow to get even subclinical ketosis.

Immune response and inflammation

An immune response is a natural consequence during early lactation. This helps the cow deal with pathogens in the uterus and infectious pathogens in the udder or teat canal, as well as to help involution of the uterus.

Inflammation is a natural part of an immune response, however, is typically a short, sharp response to resolve infections quickly. It is not advantageous to have a prolonged immune response as this saps glucose, which will have a serious impact on performance.

Recent studies have highlighted that an activated immune response can utilise up to 2kg of glucose/day, diverting energy away from production and reproduction.

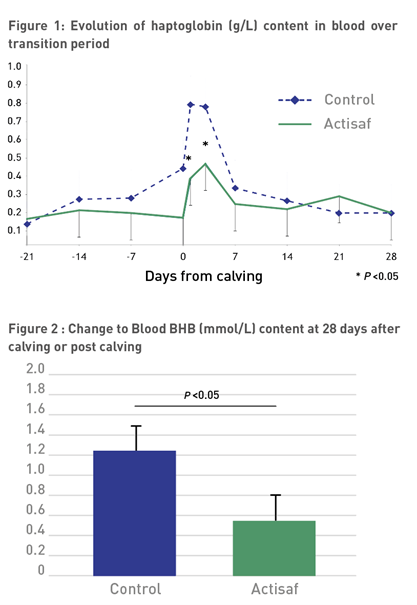

Measuring haptoglobin levels (an indicator of inflammation) during the transition period from day 0 – 14 after calving can allow the accurate prediction of disease development. As outlined above, inflammation is natural in early lactation, so even healthy cows have a significant increase in haptoglobin levels during the transition period.

Critically, however, this spike in haptoglobin levels will return to baseline levels relatively quickly in a healthy cow. Cows with severely elevated levels of haptoglobin for a prolonged period in early lactation are likely to develop serious metabolic problems.

Indeed, cows with elevated post-partum haptoglobin levels exhibit a higher risk of uterine infection or respiratory disease, a four-fold increase in the risk of metritis, a 40% decrease in the chance of successful conception during the first 150 days in milk and, typically, around nearly 1,000L less milk yield over the lactation.

Of course, increased inflammation can also be caused by pathogenic infection (such as mastitis), fatty liver disease and excessive body condition, so wider management factors are also important alongside careful transition cow nutrition.

Other factors such as handling or social stress can also pose problems, so good overall management is imperative alongside careful transition cow nutrition.

How does Actisaf help?

Supplementing dairy cows with Actisaf live yeast during transition ensures cows make a better start to the lactation, which contributes to better production and reproductive performance.

There is considerable peer-reviewed trial work to show that Actisaf supplementation reduces the risk of acidosis and improves fibre digestion and feed conversion efficiency, as well as increasing DMI, thereby reducing negative energy balance in early lactation.

This is because Actisaf increases VFA production and improves rumen pH and redox potential, resulting in more glucose pre-cursor, which is what the cow requires to address negative energy balance. This can help to reduce the risk of subclinical ketosis in early lactation.

More recent research, presented at the ADSA Discovery Conference on Food Agriculture in the US in 2019, backed this up, showing a reduced drop in DMI in the days preceding calving and higher intakes post calving, as well as higher milk yield throughout the early lactation period.

It also showed lower blood BHB levels at 28 days post-calving when cows were supplemented with Actisaf, clearly demonstrating that cows had a reduced risk of subclinical ketosis.

In addition, the trial found that haptoglobin levels were reduced in early lactation when cows were supplemented with Actisaf (see Figures one and two below).

Find out more

The dry and transition periods really are the springboard to a successful lactation. Find out more about management during the whole dry period by clicking here.