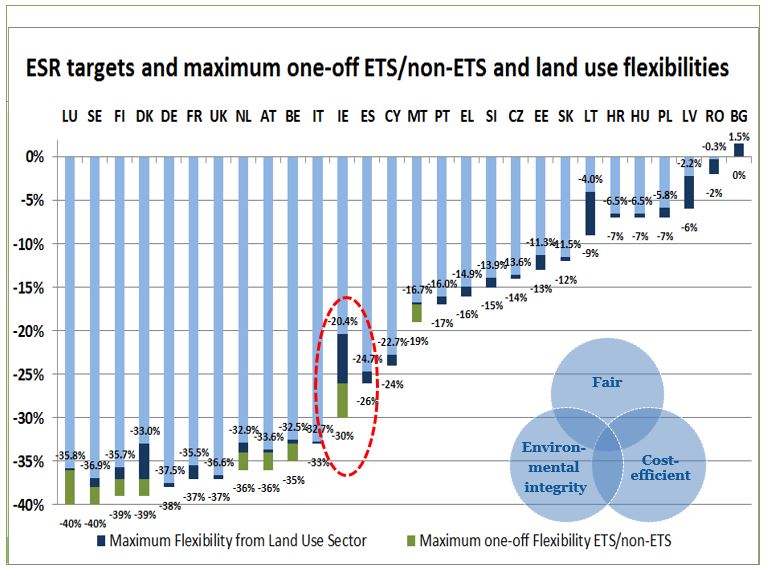

The emissions generated from Irish agriculture need to fall by 30% on 1990 levels by 2030, according to the Department of Agriculture’s John Muldowney.

However, with the inclusion of flexibility under Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF), he said, this target can drop to 20.4%.

“Those flexibilities are not free, they require policy intervention and exchequer cost to generate those credits,” he said.

The Agriculture Inspector from the Climate Change and Bio-Energy Policy Division spoke at the recent Addressing Climate Change in Irish Agriculture conference hosted by the Agricultural Science Association (ASA).

The Department sponsored the conference in recognition of the role that the ASA plays in bringing together key stakeholders from the sector to discuss the important issue of climate change.

“For Ireland to maximise the 9.6% flexibility, we will be on the margin of our ability to achieve that. Afforestation will be the biggest element but grazing and crop management will try to bridge that gap.

“We will be trying to optimise how we achieve that between our agricultural and land use measures,” he said.

The Department representative also said that the majority of agricultural emissions come from enteric fermentation with most of the rest coming from nitrous emissions from soils.

Speaking about draft projections, Muldowney said Ireland’s agricultural emissions should peak around 2025 before falling off slightly.

“They are going to be about 3% above that 2005 baseline, the challenge is to try and introduce measures to at least flat line and hopefully reduce it below that 2005 threshold.”

Where does Ireland currently stand?

Muldowney also said that Ireland has a national mitigation plan – the Climate Action Low Carbon Development Act of 2015.

That puts in place on a statutory basis the requirements for a national mitigation plan which has to be published by June of this year.

“It also puts in place the need for a national adaptation framework which is also in process for the end of the year and under the 2012 adaptation framework, the Department of Agriculture just completed its first adaptation plan for the sector,” he said.

The national climate change advisory council has also been in place since January 2016, he said, to guide the Government on what measures where possible across all sectors and the cost effectiveness of these.

How could climate change affect global food production?

Muldowney also discussed how climate change could impact on global food production.

“Globally, the impact is negative in almost every scenario, there is a downward trend of up to maybe 10% in some of our main crops of wheat and maize.

“It is that downward trend that we are very interested in trying to address.

This is against the background where the global population is rising and there is an expected need to produce 70% more food by 2050 to feed this growing population.

“So you have climate change impacting downward on food production trends but yet we have a growing population with increasing demands.

“It is important that we are able to build resilience in agriculture and try to optimise food production systems to the land type that it is most suitable to,” he said.