The parts and service arm of any manufacturing business is often considered rather unglamorous and something of a backwater in a company’s operations.

Despite this ‘worthy but dull’ image, Wolfgang Jung, retiring head of the aftersales operation at Krone in Germany, is adamant that it is vitally important, and that importance is only growing as machinery becomes more sophisticated, and expensive.

Much of Wolfgang’s career was spent with Perkins Engines, and subsequently Caterpillar, before he started with Krone.

This experience encompassed both the agricultural and construction industries, which are often considered allied, yet he sees them as being chalk and cheese from the aftersales perspective.

There are two major differences to be considered, the first is that farming is very seasonal with a frantic harvest window when tremendous pressure tends to be put on suppliers by farmers who, are in turn, under tremendous pressure themselves.

The second is that, generally speaking, construction companies tend to be businesses ran by mangers rather than owner-operators.

There tends to be a more detached view with machines run as economic units, the maintenance and running of which requires planning and timely execution.

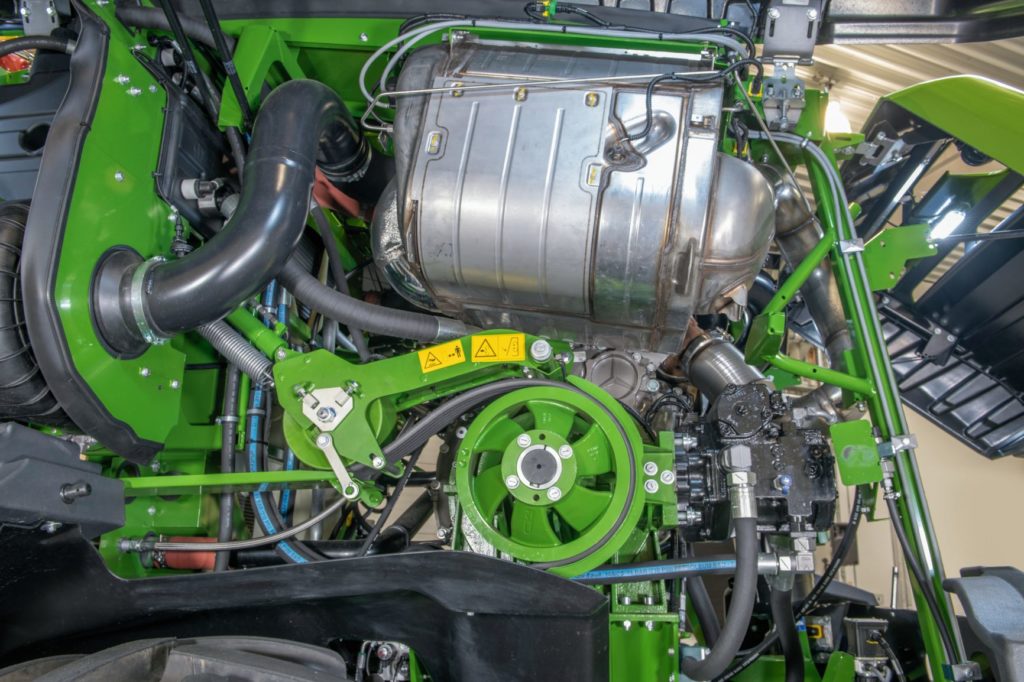

Has this been amplified by the increasing complexity of machinery and the advent of electronics?

In an interview with Agriland, Wolfgang harbours little doubt that, over the last five to 10 years, the emphasis on repairing tractors has swung to digital issues and away from mechanical problems.

Home service or specialist technician?

This is where the debate on the ‘right to repair’ rears its head. The argument of the consumer is that ownership confers the right to do as they wish to what is their property.

There is no disagreement on this point, Wolfgang assures us. All the information is there for farmers to repair machines themselves, but in his eyes, they do not usually posses the skills to do so.

“Customers could fix a high proportion of mechanical problems, but electronic problems need diagnosis and understanding of its architecture,” he explained.

This diagnosis requires new skill sets, and “a new service level and depth of training in the technicians”, he added.

Where electronic problems are concerned, he describes the need for those working on these issues, whatever the type of machine, to achieve a “critical mass of knowledge and experience”.

This is obviously easier for a dealership to acquire, as it is their job to work with the equipment on a daily basis.

The farmer, with just one or two machines on the farm, will not be able to assimilate the skills needed to service the machines properly, thus greater reliance on the dealer will become necessary, if not always welcome.

Dealers, in turn, will need to provide a higher level of service and this is will very much depend on how well they are managed.

“Dealers need to be organised” he notes, adding that there is room for improvement in many.

And it is not a question of size – smaller dealers can be as good as any if they have the enthusiasm. “Bigger may not be the best,” he added.

Supporting dealers is essential

Faced with the increasing complexity of machines, a complexity that has brought great gains in efficiency, dealers have to focus on providing value for money.

“The importers have to be as good as we are at the factory. It is my objective to ensure they have the knowledge, ability and know-how to service the machines we sell. We succeed or fail together,” Wolfgang said.

“Service is part of building sales”, is certainly a sentiment that few would argue with. Yet it is a two-way track; “Farmers have to appreciate the service and the people providing it”, Wolfgang added.

Those people will often have families themselves, and with the dwindling pool of farmers offspring, who share the farming work ethic, being available, or willing to train as technicians, finding the right staff can be problematical.

“We in the service departments are sitting between chairs,” Wolfgang continued.

The two chairs being the dealer and the customer. The dealer has commitments to both the customer and its continuing profitability, while the customer wants a tractor and implement that works 24/7 without fear of interruption.

These expectations can, and often do, conflict, yet the Krone representative does see a way ahead that is already becoming reality at ground level.

It is the construction trade which leads the way once again, by not just buying a machines, but buying that machine as part of a package that includes maintenance and repair.

Krone encourages whole life packages

Krone believes that packages are the way forward. The advantages are that the customer will have a firm idea of running costs, as well as a machine that has been serviced and maintained on a regular basis.

Budgeting for not only the purchase price, but the operating costs as a whole, should lead to a longer, less troublesome life and, hopefully, an enhanced value when it comes to selling.

‘Packaging’ it all into the one transaction makes management easier and the machine more cost-effective according to Wolfgang.

However, he does appreciate that many farmers are still resistant to the idea, but feels that will reduce over time.

Professional parts operation

If the servicing scene is changing then so is the parts side of the equation. Yet the basics remain in place, there is still the need for the parts to be on the shelf ready for immediate delivery.

With regards to the present reported shortage of components, Wolfgang feels that the company has weathered the storm well so far, and has kept its inventory of parts up to an acceptable level, although there is no room for complacency.

The generally held reservation about the fragility of electrical components exposed to conditions is not as valid today as it was.

“10 or 15 years ago there were many problems with sensors, cables and connectors; many of these are history, the industry has learned and engineers have reacted,” Wolfgang continued.

Yes, there are still failures, but these are declining in number and there is a constant dialogue between the the parts department and the design engineers in a bid to refine reliability, and also serviceability, he maintains.

Parts and service are, to his mind, an essential element of any company’s activities.

He points to the millions spent by Krone in investing in this part of the business and feels that this is now paying off.

Krone, Farmhand and the family firm ethos

The training of the dealers and their staff is vital, and that not only includes the service technicians, but also management methods for the various departments within a dealership to ensure the efficiency of the whole company.

In many countries, Krone owns the importers, but not in Ireland where Farmhand remains an independent family-owned firm.

This is a situation much to Wolfgang’s liking for he points out that “when buying a Krone machine, you are buying the into the Krone family, and Farmhand are already part of that family”.