The potential for land-use change on Irish peatlands and land under forest cover is low, according to the recently published Land Use Evidence Review Phase 1 Synthesis Report.

Natural characteristics and/or current land use can restrict the purposes for how land can be used, the report, which assessed the land-use change potential for grassland as medium, states.

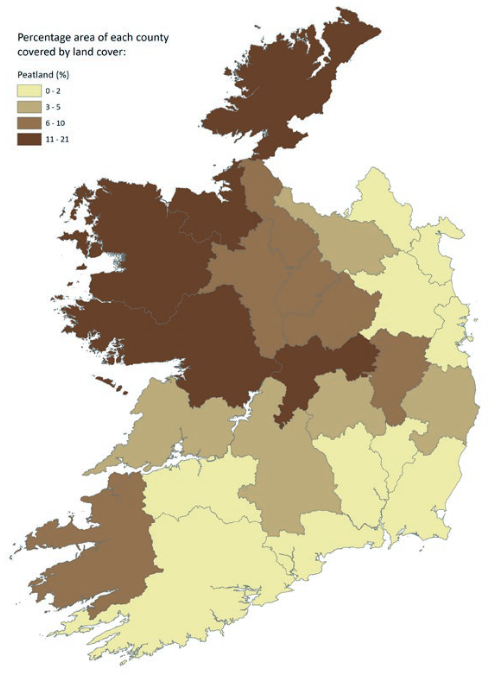

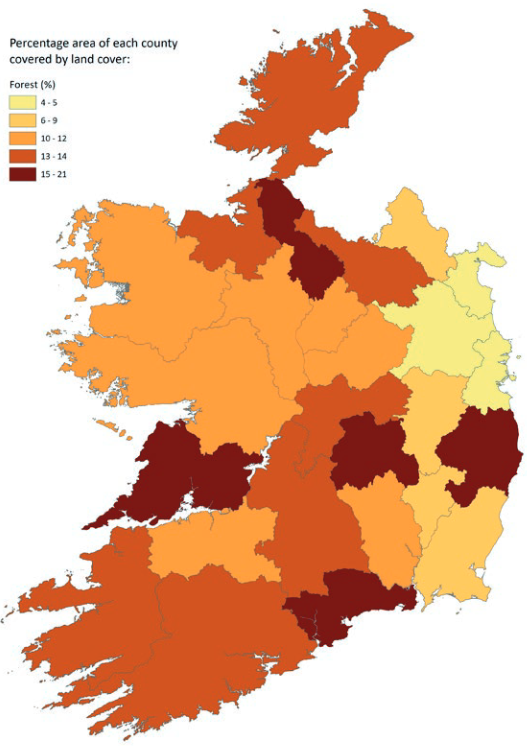

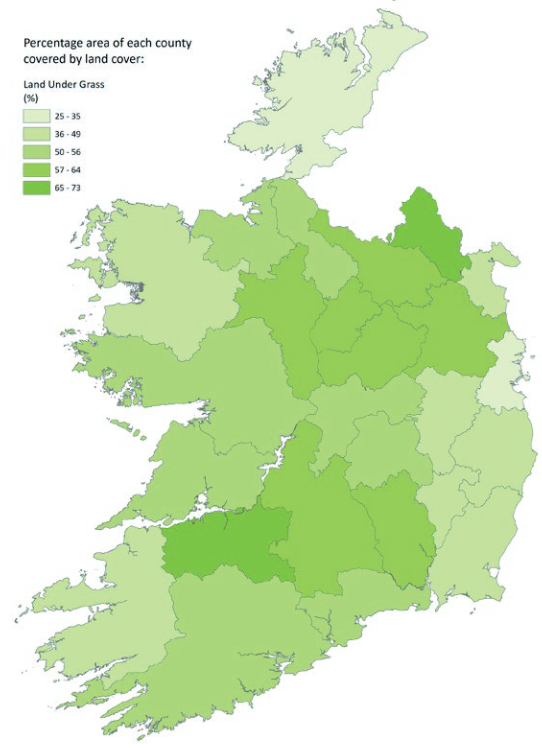

Currently 52.4% of Ireland’s land area is under grass (36,777km2), 6.5% under peatland (4,595km2), while 12.3% is under forestry (8,623km2), according to the review.

The report will inform Ireland’s sectoral emissions ceiling for the land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector which includes soils, trees, plants, biomass, and timber.

Under new EU rules, Ireland has been allocated a 3.73 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent ceiling for LULUCF. The Irish sector is currently a net source of carbon, rather than a sink.

Peatlands, forests and grassland

The midlands and the west account for the highest percentage area of peatlands compared to the south and east, including, bare peat and fens, blanket bog, cutover bog and raised bog.

Co. Dublin has the lowest percentage area under grass nationally at 25%. At an average of 54% outside Dublin, Co. Donegal (35%) has the lowest area and Co. Monaghan (73%) the highest.

On average, each county has a forest area of 12%, with the lowest percentage area in Co. Meath (4%) and the highest in Co. Wicklow (21%), including coniferous, broadleaf, transitional and mixed forest.

The review notes that a different approach (mapping) has been used to estimate forest cover than in the National Forest Inventory, which states that Ireland’s forests reached 11.6% of the land area.

While forestry has been a major carbon sink mitigating LULUCF emissions over the last number of decades, CO2 levels absorbed by forests have declined since 2000, the report states.

Ireland’s forests have shifted towards being monocultures used for timber production since the late-18th century at the unintended expense of forest biodiversity, according to the report.

Thus the review recommends the development of a land classification system for Ireland that includes a forestry classification that is not solely focused on forests for timber production.

Most trees between 1990 and 2006 were planted on wetlands, which then shifted towards afforestation on agricultural land from 2006 to 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said.

While forestry provides an important habitat for certain species, conversion of land from other land uses to forestry can have detrimental impacts on other species, the report warns.

Agricultural land

Agriculture is Ireland’s dominant land-use class and accounts for 67% of Ireland’s land cover, most of this is grassland, used for pasture, hay, silage and rough grazing.

While the national percentage of agricultural land cover has remained consistent since 1990, there have been changes to Ireland’s agricultural land which has been created from draining of wetlands.

Decoupling Ireland’s agricultural activities, and planned growth, from environmental damage is a significant challenge, according to the report which also states:

“It is in the long-term interest of agriculture to transition to a model that supports a high-quality environment so that soil, water, climate and biodiversity conditions are adequate to support farming into the future.”

While land under grass may pose relatively fewer physical barriers to a change in land use, there are significant economic implications in Ireland for such change, the report states.

Targets included in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and Ireland’s Food Vision 2030 strategy, among others, encourage agricultural practices that are environmentally and economically sustainable.

Agroforestry, which encourages grazing and cutting silage and hay while growing trees for timber in the same field, may involve changes in land use on what is currently under grass, the report states.