Lameness is a huge problem on sheep farms, especially this time of the year when animals are being housed and when in-lamb ewes are purchased.

Tom Coll – a Teagasc advisor – spoke about lameness on farms and what can be done to minimise it at a sheep seminar, in Manorhamilton, Co. Leitrim, on Monday night.

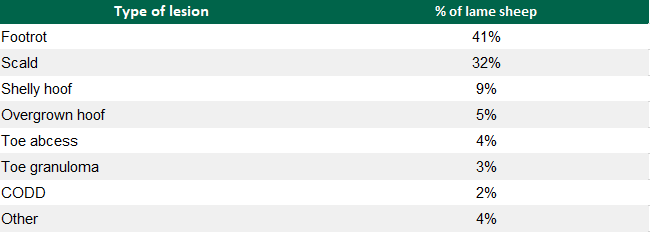

He said: “Teagasc carried out a study over eight years ago on the causes of lameness on sheep farms in counties Sligo and Leitrim. As you would have thought, footrot and scald were the most predominant.

“On average, 9.93% of the flock were lame, which is above the target of no more than 5%. However, compared to other areas in Ireland, the land around here is quite heavy and wet which doesn’t help when it comes to controlling lameness.”

Footrot was the main contributor to lameness on sheep farms in the two regions at 41%, according to Coll.

He added: “The key message is you are never going to eliminate lameness from your flock completely. However, you can minimise it.”

Listed (below) are the main causes of lameness on sheep farms in counties Sligo and Leitrim.

Types

Coll explained: “The two main causes of lameness – as already mentioned above – are scald and footrot on Irish sheep farms. Scald – which is very common in lambs – is caused by a naturally-occurring bacteria called Fusobacterium necrophorum.

“Scald is mainly an issue on rough pastures and is more than likely going to develop in sheep when they are exposed to wet pastures. Furthermore, scald is the first stage of footrot.”

- Footrot. Image source: Teagasc

- Scald. Image source: Teagasc

- CODD. Image source: Teagasc

He added: “Next up is footrot, which can survive up to 12-14 days in sheep. It is caused by a bacteria called Dichelobacter and it has a foul smell.

“It has the ability to spread rapidly – especially in straw-bedded pens during the housing period.

“Moreover, contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) is commonly found in sheep purchased from the mart and, like footrot, it has the ability to spread quickly.”

Treatment

Coll mentioned that hill flocks are at an advantage when it comes to preventing lameness because the bacteria that cause scald and footrot can’t survive in the acidic soils on the hills.

This, in turn, is the reason why there are fewer incidences of lameness in hill flocks compared to lowland sheep.

Coll explained: “The best time to treat sheep for foot problems is when they are being housed for winter or at weaning time.

If you plan to run sheep through a footbath it should consist of either 1kg of zinc sulphate or copper sulphate and mixed with 10L of water.

“Furthermore, the ewes or lambs should be allowed to stand in the solution for at least three minutes. Straight after, the flock should be allowed to stand on clean concrete for at least one hour. It is best practice to avoid muddy areas post-treatment.”

Best practice

The aim should be to have less than 5% of the flock lame. It is important farmers treat sheep correctly, as in the case of footrot an antibiotic is needed to treat it as a footbath won’t cure it.

In the case of any bought-in sheep, they should be isolated from the rest of the flock and monitored for up to three weeks for any signs of health problems.

Also, it is best to avoid trimming hooves. Toe granuloma is caused by hoof trimming and it is more than likely that the farmer will have to cull any sheep with this problem as it is difficult to cure.