Deputy Michael Fitzmaurice took issue recently with the European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development Phil Hogan’s statement that farmers in the west of Ireland “need to be incentivised to switch from sucklers to forestry or biomass production”.

It brought the issue of forestry and Government policy on the matter to the fore and highlighted the need for a more robust debate around the whole area of policy, tree type and suitable conditions for afforestation.

Meanwhile, the commissioner made the comments during a recent Irish Rural Link conference entitled ‘Climate Change: Opportunities for Rural Communities’.

Fitzmaurice, while commenting on the matter, pointed out that farmers in the west of Ireland needed “to wake up to the policy being pushed by Hogan and the Fine Gael party”.

Does Commissioner Hogan and his colleagues realise that not all land in the west is suitable for forestry or biomass production?

Fitzmaurice continued: “I have seen first-hand where crops of willow or miscanthus have not returned anywhere near the expected yield in eastern parts of the country; so how does Fine Gael expect these crops to grow in lesser quality land in the west of Ireland?”

So, what is the policy on forestry in this country? And, more importantly, what, if any, is the onus of responsibility on farmers and landowners to plant their land in the first instance?

The tree of knowledge

In a statement to AgriLand, the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine pointed out that Ireland’s forestry policy has undergone a number of “significant changes in emphasis” since the foundation of the state.

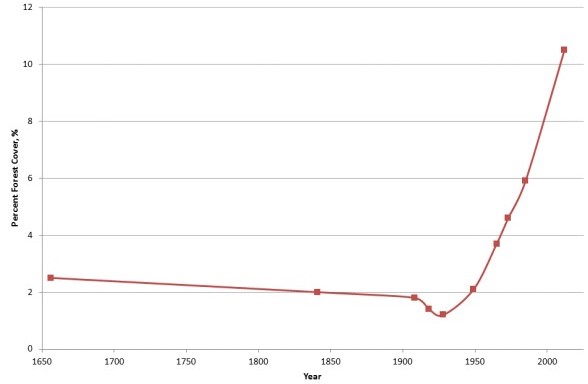

Prior to that, forest cover represented approximately 1% of the land area.

The graph below shows forest cover in Ireland from 1656 to 2012.

The department also highlighted the fact that the emphasis on forestry in this country began back in 1959 when the first Programme for Economic Recovery placed an obligation on the state to plant 25,000ac (10,000ha) per annum with a target of one million acres – 400,000ha – over a certain period of time.

A spokesperson told AgriLand that the one million acre target was reached in 1993.

The introduction of the Western Package Scheme supported by EU Funding in 1981 saw the first of many initiatives to support afforestation by the private sector and in particular by farmers.

He continued: “The scheme had limited success – a review in 1985 highlighted the lack of annual income as being one of a number of reasons.

“In 1987, a scheme of compensatory allowances was introduced and provided annual payments for 15 years. It was amended the following year to increase the annual payment period to 20 years for broadleaves.”

Hedge map

Meanwhile, in 2010, Teagasc developed a hedge map based on 2005 colour orthophotography.

In 2005, the total area of hedges, trees and scrub outside of the forest was 482,000ha or 6.9% of the total land area of Ireland.

Policy and best interest

A recent review of the country’s forestry policy states that a range of national and EU legislation has impacted on forest policy in Ireland over the past two decades.

The report concluded that in order to reach a scale of timber production large enough to support a range of processing industries, the national forest estate would need to increase to 1.2 million hectares – 17% of total land area – by 2030.

The table below, meanwhile, indicates the country’s forest area change since the foundation of the state 1922-2012.

‘The only constant is change’

Last January, the Irish forestry industry forecasted that it was set to double its supply of raw material by 2035.

The business sector also pointed to the fact that it was on target to create an additional 6,000 rural jobs on top of the 12,000 jobs already driven by the industry.

“21,000 forest owners who supply the raw timber product – as well as the many timber contractors and hauliers that harvest and transport it to the sawmills – will earn an estimated €6.4 billion which will serve as a further boost to rural economies,” a spokesperson for the association concluded.