There have been a number of economic outlook publications recently outlining perspectives on Irish economic recovery post-pandemic and as Brexit impacts evolve and what that might mean for the agri-food sector.

There is more than irony in the fact that this assessment of Irish economy resilience comes at a time when the very existence of the agri-sector – the biggest contributor to Irish economy activity (rather than to GDP which included multinational profits) – is under threat.

As the chart below shows, spending by the food and drink sector in the Irish economy is over five times greater than that of the next biggest spender – the pharma sector.

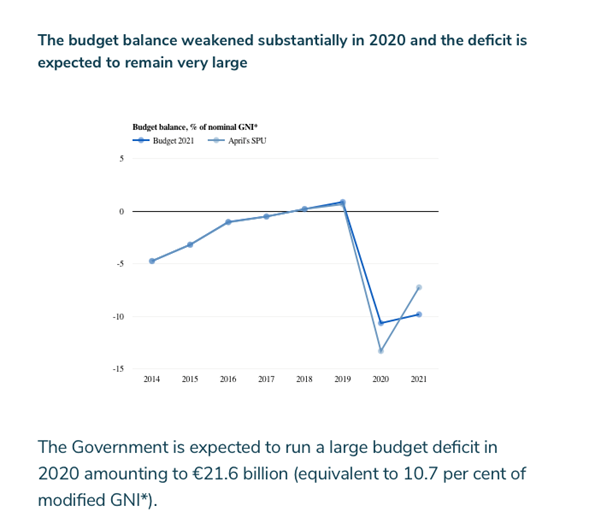

The core of many of these outlook analyses is focused on the eventual size of the public spending deficit in the economy, and the speed of Irish economy recovery in the short-term, and some of the headwinds or threats to this recovery in the medium-term.

Agri-food sector economic impact

The Irish agri-food sector, despite the Covid-19 pandemic challenge on farm and food businesses and in local and export markets, managed to process and sell all of the country’s farm output in 2020.

This generated spending of €6 billion in the Irish economy, while earning over €13 billion in export values, thus maintaining employment for 260,000 people across the rural and regional economy.

This performance also has to be seen in the context of the evolving Brexit impact on the sector.

Indeed it is in stark contrast to our near neighbours in the UK, who had to pour a lot of milk down the drain because of the closure of their food and hospitality sector in the first lockdown in March and April last year.

If the Irish agri-sector had not had the capability to find markets across 150 countries globally for our food output, then not only would the €13.5 billion in export earnings have been lost to the state, but the state would also have had to incur the cost of billions of Covid-19 payments.

So, instead of an anticipated €21 billion in borrowings, as set out in the chart below, a figure of double or treble this would be staring us in the face over the long-term.

Resilience of agri-food sector

This huge positive fiscal impact from agriculture’s resilience seems to have been taken for granted by Irish economy analysts and the climate activist lobby.

The key point is that business resilience, whether during a pandemic or under global economy supply and demand volatility, is hard earned and cannot be taken for granted.

It requires very significant commitment and coordination, not just in the production and processing of food, but also in having a final product that meets demand for food across 150 countries.

This huge capability has not only been underestimated and dismissed in the characterisation of the agri-sector’s performance over the last number of years, but is completely absent from the assessments of the future of the sector in the context of climate action lobby rhetoric.

Any ambition to increase production and exports in dairy, meat, consumer foods, drink or seafood has had to be based on verifiable demand for each product category, validated by detailed market analysis by product type and region.

Not only did this matching of supply aspirations with real demand opportunities clarify policy, it also better defined business risk, which is a key element in assessing the financing and investment challenges from the Food Harvest/FoodWise analyses.

Neither an individual farmer nor a food processor is going to secure finance from the Irish banking system to maintain their business, unless this business risk issue is explicitly managed and planned for.

Economic stability

Economic sustainability in the Irish agri-food sector in the future, as in the past, faces very immediate price and income volatility and financial resilience challenges.

Any credible assessment of the Irish agri-sector must assess and prescribe for business risk, economic sustainability, price volatility and access to finance and investment.

The environmental coalition policy document is deafeningly silent on the issue of economic sustainability or resilience.

The concept of business risk, or the very real challenges for the agri-sector of price and income volatility, and how this frames access to investment capital, is totally absent from their policy considerations.

Because of this very large omission, there is no balancing assessment or any credible practical detail relating to production capacity, processing capability, market and distribution challenges or market access.

Food exports

A key thread to the documents is the opinion of the coalition, that exporting food is not a good thing.

This is despite all assessment of the Irish food sector and Irish manufacturing in general over the last 30 years, emphasising the need to find export markets to achieve scale, given Ireland’s extremely small population / domestic market.

In reality the Irish agri-food industry only survives and supports 260,000 jobs, €16 billion Irish economy spend and €14 billion in exports, because it manages finance and investment risk and volatility.

It is also due to consumers in the Irish domestic market and across 150 countries, buying its products year in and year out.

Irish agriculture is resilient and this resilience fundamentally underpins the bankability of the sector. The environmental coalition may not value resilience or bankability, but the Irish economy and its economic recovery do.