The coincidental publication of the 2030 Agri-food Strategy proposals for public consultation this week and the striking out of An Taisce’s High Court appeal against planning permission granted to Glanbia / Royal A-Ware for a cheese plant in Co. Kikenny, demonstrates a glimpse of the extremes of how national policy, particularly agri-food policy, can be developed and implemented, or not, as the case may be in Ireland.

National policy, not just in terms of climate change but in trade, economics and agricultural production.

The broad challenge here is whether a national response to an external economic shock such as Brexit and indeed all future economic development policy, is to be framed by means of an inclusive, if sometimes long drawn-out, adversarial process such as the 2030 Agri-Food Strategy or the Climate Action Bill.

A process that takes inputs from government departments, the broad agricultural sectors, farmers, farm organisations, environmentalists, processors, state agencies and state regulators.

Influence on development of agri-food policy

On the other hand, will it be on the whim of an interest group such as the Environmental Pillar, which has decided not to participate in the dynamic of an open engagement process, and ultimately declared that their opinion trumps that of all others, including the government, which is broadly dismissed as either misinformed or tainted by self interest?

Given the timing of the High Court judgement [Glanbia cheese plant], coinciding with the launch of the Agri-Food Strategy process and the framing of the climate bill in the Dáil, it might be tempting to see the High Court judgment as a commentary on environmental policy challenges and dilemmas solely.

In truth, the core purpose of the €140 million investment, was as a diversification strategy to offset and rebalance our dependence on the UK market for cheddar cheese, in the context of the UK exit from the EU and the Single Market.

The primary purpose of the investment was thus the avoidance of the potentially dramatic decline in returns for Irish producers and processors, that continuing dependence on a now third country market, could present for Irish farm incomes.

Market diversification

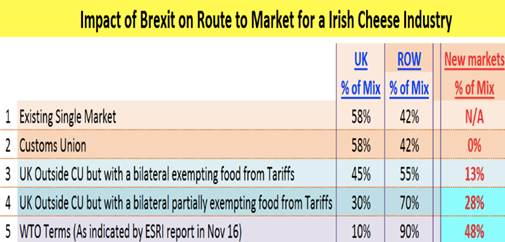

In 2016, the four major cheese manufacturers and Ornua met with government and presented a number of scenarios (as set out above), that highlighted the range of negative outcomes for Irish dairy farmers and the dairy industry as a result of the UK decision to exit the EU.

Moreover, the scenarios presented were based on a range of analyses by state agencies, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) and EU Commission, as were similar concerns for the beef sector, post-Brexit.

The Glanbia Belview joint venture (JV) with A-Ware, would effectively remove 450 million litres of milk from the UK cheddar pool and instead make 50,000t of Gouda and Edam available for sale in EU (non-UK) and international markets across the globe.

While the Glanbia / A-Ware investment is the biggest market diversification project arising from the Brexit challenge, it is not the only one, with major projects and JVs being announced with Norwegian Jarlsberg by Dairygold, and in mozzarella by Glanbia and Carbery.

The concern has to be how close the action against the continental cheese plant came to undermining, not just investment on behalf of farmers but very clearly, government policy and actions to mitigate an economic shock like Brexit.

Discussion and negotiation

Both the 2030 Agri-Food Strategy process and the Climate Action Bill present huge challenges for the Irish economy and the agri-food sector in particular, with a huge concern among producers, based on performance to date, that EU and government policy will be heavy on the regulation and light on cost / income support in particular.

Also proving challenging is the potential post Covid-19 economic outlook and the question mark over the longevity of Ireland’s low corporation tax policy.

In addition to the debates and considerations across the various democratic interfaces in Irish politics, these matters will also be subject to scrutiny and analysis in the EU discussions on Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform, the EU Green Deal and the rollout of the EU recovery fund.

Ireland, or indeed Irish agriculture, may not get the bounce of a ball across all of these debates or discussions, but we don’t have the luxury of deciding not to participate and to sit back and litigate the outcomes we don’t like or approve of.