The standard four-stroke engine has served humanity well and continues to do so, but it is not the only format available to engine designers; the opposed-piston two-stroke is now ripe for a comeback.

Great strides have been made over the years to bring the present crop of internal combustion engines to a degree of performance that would have been unthinkable just a couple of decades ago, yet there may well be room for another large leap forward.

Proven and reliable

All the engines that we see today are of the same basic design; a piston moves up and down its own cylinder four times for each power stroke, with the fuel and gasses being controlled by valves and injectors.

The reciprocating motion is converted to rotary motion via a crankshaft and the basic differences between engines are the number and size of the cylinders.

This arrangement has been around for nearly 150 years so it must be the ultimate design, however, it isn’t, as there is another well-established layout which has been shown to be better still.

Old kid on the block

The challenger has been around for almost as long as the Otto cycle four-stroke unit itself and comes in the form of the two-stroke opposed-piston engine (OPE), which sounds complicated but it is in fact a good deal less complex than a four-stroke with all its valve gear.

The theory is simple enough; instead of having a single piston moving up and down each cylinder there are two, one at each end, and combustion occurs between them rather than on top of them.

In true two-stroke fashion the flow of gasses is controlled by ports in the cylinder wall which are uncovered by the passage of the piston skirt as it travels past them.

The lack of cylinder heads and valve train also makes the engines more frugal – a 5-10% improvement in thermal efficiency is generally accepted as the norm.

Lubrication issues

There are two immediate problems with this design. The first is that two crankshafts are needed, one at each end of the cylinder bank, while the second is that two strokes have traditionally relied on total loss lubrication, a method that simply cannot be entertained nowadays due to emission regulations.

However, much ingenuity has gone into solving these issues with various mechanisms and layouts being designed to transmit the power to a common crankshaft, while dry-sump lubrication takes care of getting oil to where it is needed.

It might also be noted that diesel fuel itself is an excellent lubricant and the technology behind keeping moving surfaces from welding themselves together, known as tribology, has advanced considerably, so this is no longer considered an obstacle to general adaption of the engines.

Lighter and cheaper

And there are good reasons why they should be adapted, including fewer moving parts, a greater power-to-weight ratio, increased thermal efficiency, easier servicing and reduced manufacturing costs.

This latter is an important factor for the breakdown of costs in building a normal four-stroke engine and suggests that big savings can be made for and, in addition to only having to produce half the number of cylinders, OPEs have:

- No cylinder heads or high pressure gaskets which can account for 7% of the cost of a standard engine;

- There is no valvetrain, 6% of the standard cost;

- 32% lower material weight;

- 33% reduced machining time;

- Reduced assembly time and half the number of expensive injectors;

- 34% lower part count

OPEs from the past

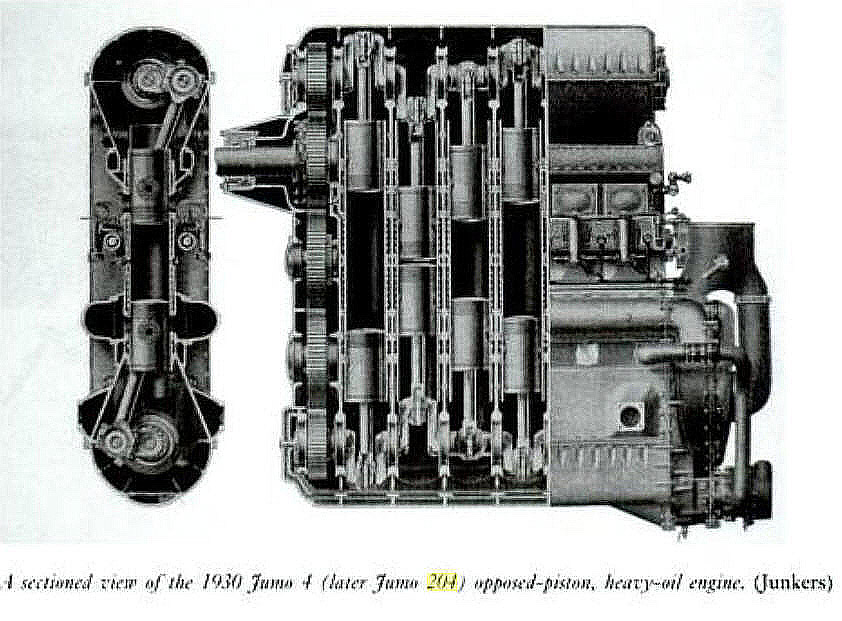

As already mentioned, these engines have been around for a long time. It was the Jumo 207 opposed-piston diesel unit which powered the high altitude Junkers JU86p reconnaissance aircraft during the war, an engine which first entered service 90 years ago.

Since then the concept has been readily adopted by the marine industry with manufacturers such as Doxford and Fairbanks Morse making engines of 20,000hp or more, while the best-known variant of all is the Napier Deltic, powered the Royal Navy’s Hunt class minesweepers and British Rail’s Class 55 ‘Deltic’ locomotives.

There was also an attempt to power a tractor with a 30hp unit by a French company just after the war. Manufacture d’Arnes de Paris, better known as MAP, boldly produced one in 1946, yet struggled to sell the machine with its novel powerplant.

This difficulty led the company to sell the factory to SOMECA, which immediately abandoned its production and used the tooling to build conventional models licenced from Fiat instead.

Backed by Cummins

With such a legacy and well-proven track record it might be asked as to why engine companies have not yet stepped out of the box and paid serious attention to the concept.

There is one that already has, and that is Cummins which, in partnership with Achates Power Inc. of Califonia, has been awarded a contract by the US army to develop a new family of diesel engines for combat vehicles based on opposed-piston technology.

While it might be argued that the commercial diesel engine market is not ready for such a revolution, it pales in comparison to the radicalism of trying to do away with the internal combustion engine altogether.

Another factor in companies wishing to stay loyal to standard four-stroke engines is that huge amounts have been invested in their production and to switch to a new format may play havoc with their medium- to long-term business plans.

Commercial considerations

Long gone are the days of manufacturers simply swapping engines about to create new models by the following weekend.

Each new advance is carefully assessed by both engineering and marketing departments before release, and the thought of a whole new engine type with the need to first sell it to the public and then back it up with service and parts will give company management many sleepless nights.

Yet it is also true that the standard engine configuration is running out of development potential.

For many years now, engineers have been saying that all the research and development money has been going into chasing emission standards rather than making fundamental improvements to the basic concept of internal combustion.

The re-emergence of the opposed-piston engine may well give companies the incentive to reconsider their position, especially if they become available off the shelf from third-party manufacturers like Cummins.

The time for a total rethink on the internal combustion engine may be long overdue.