With Brexit looming, Ireland needs to broaden its horizons on the global food market.

Instead of being an island at the “centre of the world” as Taoiseach Leo Varadkar envisages, our food industry could find itself a food-exporting nation on the periphery of Europe.

The Taoiseach announced a plan in August to double Ireland’s Global Footprint by 2025, by opening new consulates and embassies worldwide. From an Irish food and farming sector perspective, this initiative can’t happen fast enough.

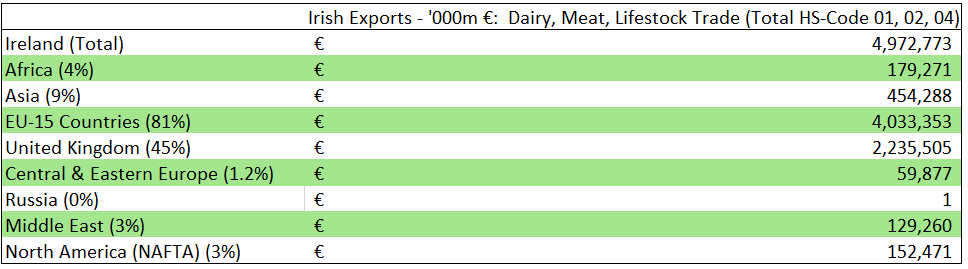

Ireland’s dairy and livestock food trade figures paint an alarming picture of an over-dependence on the British market. 45% of Ireland’s €4.9 billion of livestock, meat, and dairy-related exports in 2016 were destined for the UK.

This figure is troubling, especially with Brexit looming. Also of concern, 81% of these Irish exports find a home in western European (EU-15) markets. Having joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973, these figures show a narrow view to trade in an expanding global market.

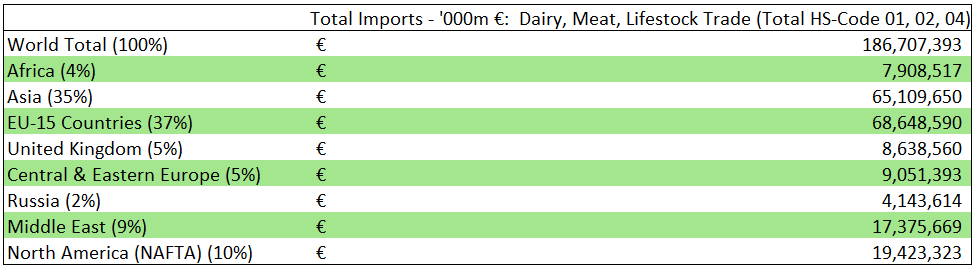

With almost two fifths of global livestock, meat and dairy trade, western Europe is still the most important trade market globally. However, Asia is where the real action is taking place.

Asia, with €60 plus billion in livestock and dairy related trade, will soon surpass the EU as the leading export destination.

Europe has seen trade of these products grow by just €4 billion in the past five years, but corresponding Asian import growth has seen a massive €23 billion jump.

One tenth of Ireland’s meat and dairy export values were destined for Asia in 2016. Ireland is now the second largest exporter of infant formula into China. With the Japanese opening up to dairy and beef trade, this will also present new market opportunities to capitalise on.

Building €0.5 billion of Irish dairy and meat exports should be a focus for trade growth over the coming years.

Central and Eastern Europe markets

However, closer to home there are other markets which need to be exploited. Collectively meat, livestock and dairy imports into Middle East countries skyrocketed from €5 billion in 2005 to over €20 billion in 2015. However, only 3% of Irish-related imports, or €129 million were destined to this region in 2016.

Ireland’s lack of a strong food trade footprint in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is perhaps the biggest disappointment.

The expansion of the European Union eastward has almost trebled the trade of livestock and dairy-related products across the region, up from €3.5 billion in 2006 to about €9 billion today.

Yet, only 1.2%, or €60 million of Ireland’s exports of these products were destined for this region in 2016. With the exception of Ukraine, nine countries in this block are European Union members. In turn, the Trade Association Agreement between the European Union and Ukraine came into force in recent weeks on September 1.

This further opens opportunities for Irish companies to a new European market with a population exceeding 42 million people.

Total food and beverage imports into Central and Eastern Europe have increased from €22 billion 10 years ago to €51 billion today.

Neighbouring Russia has a similar population of 143 million and combined GDP of $1.5 trillion. Russia’s food and beverage imports are smaller than CEE, reaching only €22 billion last year. Much was made in Ireland of Russia’s food sanctions in 2014. 60% of Russia’s GDP and population are located in its logistically accessible western and northern regions.

Yet, the four largest EU countries in CEE countries have an even greater GDP and buying power than Russia’s economic centre. Consequently, why hasn’t as big a fuss been made about the growth opportunities for Irish products across the CEE region?

The Irish government needs to incentivise a consolidated approach at a national level to efficiently promote a strong value proposition for Ireland’s dairy, meat, livestock, food product, farm machinery and related services sectors as one unique marque. If Irish farmers are to fully benefit from export growth, some joined thinking needs to be applied to new markets.

In other words, rather than worrying about the markets that are diminishing – which potentially includes a post-Brexit UK – they will focus more on the markets that are there for the taking.