Improving on-farm sustainability isn’t just one thing; it’s a combination of lots of little things.

This was proven on the farm of Trevor and Olive Crowley – located just outside Lissarda, Co. Cork – who were the hosts of this year’s ‘Dairy Sustainability Day’, which was held last week.

The Crowleys were chosen to host the event because of their continued efforts to reduce their carbon footprint, along with being awarded the Bord Bia 2018 Origin Green Award last year.

The event offered farmers the opportunity to see first-hand what is achievable from an environmental point of view, without the need for any additional costs.

Between 2016 and 2017, the family reduced their carbon footprint per kilogram of milk solids (MS) by 18%. This was achieved through a combination of a longer grazing season, a reduction in nitrogen application and reduced manure emissions from less days housed.

Herd performance

Over the last four years, the farm has grown in numbers from 100 to 150 cows on a 68.8ha grazing platform.

Last year, the farm achieved 6,010L/cow and supplied 483kg of MS/cow. This was met by a protein percentage of 4.21% and butterfat percentage of 3.59%.

The farm is also achieving a calving interval of 367 days, a six-week calving rate of 80% and is calving 100% of its heifers between 22 and 26 months-of-age.

Despite all this, there is one downfall. The EBI of the herd is low at just €89; this is €9 below the Dairygold average.

The EBI system has a significant roll to play in reducing the environmental impact on dairy farms. According to studies conducted by Teagasc, a “€10 increase in EBI can lead to a 2% reduction in carbon footprint”.

Speaking at the event was Teagasc’s Stuart Childs, who said: “If you work off the science of EBI, Trevor could earn another €4,000 to €5,000 if he got as far as the Dairygold EBI average; along with a further 2% reduction in his greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – by virtue of higher efficiency.”

Water Quality

During the visit, Ciara Donovan from Dairygold spoke on the topic of water quality and what the Crowleys are doing to protect it.

Firstly, Ciara touched on why there is such a need to protect water quality, by saying: “Only 57% of our rivers and less than 50% of our lakes are satisfying the EU regulation requirements – which is very worrying.

Since the publication of that report in 2015, there has been a 3% deterioration in water quality.

The Crowley family have implemented a number of measures to protect the water courses around their farm.

One thing they do, Ciara explained, is: “They protect any critical source areas (CSAs). They do this by not spreading any slurry on one field which has a steep hill leading into a man-made lake.”

In addition, Ciara added that chemical fertiliser is only spread when “growth is good” and the weather conditions are dry.

In relation to buffer zones, she said: “Trevor leaves what he calls a ‘poverty area’ when applying fertiliser or slurry.

“For slurry, Trevor stays more than 5m out from anything; whether it’s a road, drain or ditch and for chemical fertiliser he stays 2m out.”

A few years ago, due to the nitrates derogation, Ciara explained how: “Trevor fenced 1.5m from his rivers – which has now overgrown – and these overgrown areas beside watercourses are very useful, because any nutrients that do run off are taken up by the over growth along the ditch.”

He also soil tests every three years which allows him to target slurry to the soils low in phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) – which he applies using a trailing shoe.

Although the trailing shoe allows him to get out a little bit earlier to spread, he still has an extra “three-weeks’ slurry storage, so he is not under pressure to get the slurry out and can apply it when he needs it or when conditions allow”.

“Trevor also ensures that all his grey water is collected and the diversion pipe coming off the silage pit has a viewing point that allows Trevor to assess the run-off before it is diverted off,” she added.

Biodiversity

Next up was Teagasc’s Daire Ó hUallacháin who discussed how Trevor has promoted biodiversity on his farm and how other farmers should do the same.

“The farm we have here is a typical intensively farmed farm from a biodiversity point of view. When you look around, the dominant habitat here is hedgerows.

“On the average intensive dairy farm, there are around 6-7km of hedgerows, which is pretty good,” he said.

However, the quality of many hedges is “sub-optimal” due to over-cutting and removal.

To improve the quality of our hedgerows, he said: “Farmers should only trim the sides of the hedges and allow the top to grow taller.”

Then, bringing the group’s attention to the quality of the hedgerows on the Crowley’s farm, he said: “The hedgerows here are thick and full of life and they have allowed the tops of the hedges to grow upwards”.

Looking around, the next dominant habitat on the farm is drains – “with about 2km on the farm”.

These are also good from a biodiversity point of view, because of conductivity, which means they connect different habitats with one another.

According to Daire, the next “Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is going to require that a certain percentage of land area is designated as habitat and it is important that farmers which achieve this percentage are rewarded through their green payments”.

In relation to the promotion of biodiversity on Trevor’s farm, he said: “It is great to see a farm not fencing right up to the butt of the hedge which gives the flora and flowers a chance to grow – which plays an important roll for pollinators.

“Particularly during this time of the year when there is not that much colour in the hedgerows.

“This is what is important from a biodiversity point of view and from a marketing point of view, because it’s promoting this clean green image along with protecting species.”

The Future

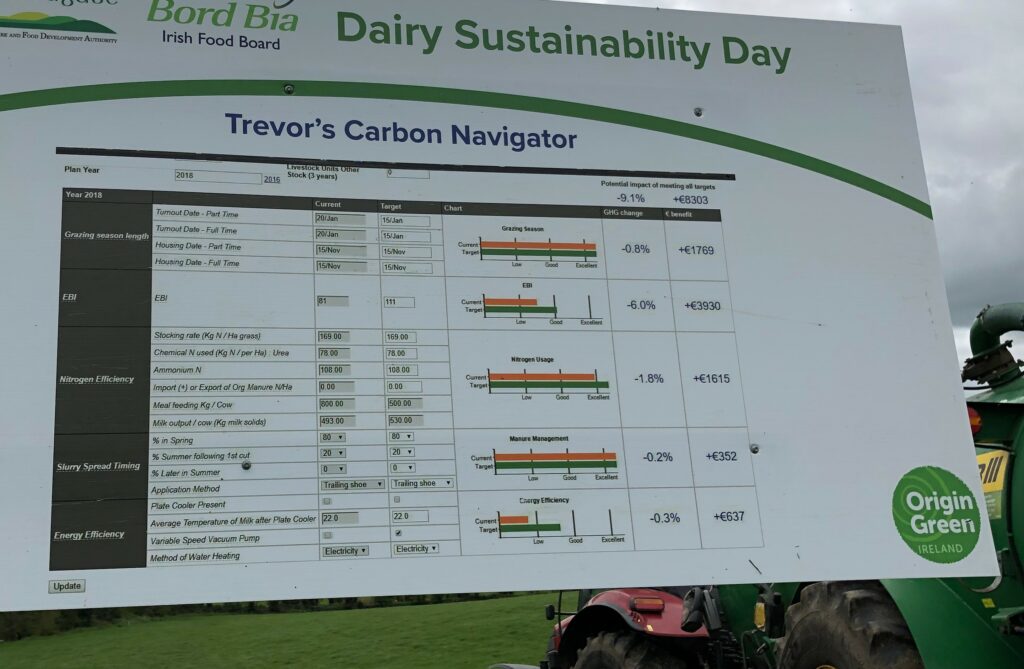

To conclude the event, Teagasc’s Stuart Childs ran through Trevor’s carbon navigator.

“He is not going to gain a huge amount in terms of grazing management because he is quite an early grazer and because of the hedgerows he is able to get cows out early due to the shelter from these. But, he would like to push turn-out back to January.”

According to the carbon navigator, this would mean a reduction of 0.8% in GHGs or a benefit of €1,769.

“In relation to EBI, we have already spoke on what he could gain here – almost €4,000.

“The total chemical nitrogen (N) won’t change too much – because his stocking rate has gone up – but the type of N he is using is going to change – as Trevor intends to switch to protected urea for the mid-season.

“He is also hoping that he can get a little bit more out of the cows in terms of production and push this up to 530kg of MS/cow,” explained Stuart.

As the carbon navigator shows, this, along with a reduction in meal feeding, will mean another €1,615 in his pocket and a GHG reduction of 1.8%.

Looking at the slurry management, because he has been using the trailing shoe, he has been able to get out a little bit earlier in the spring time and is losing less N to the environment.

“He is also using a heat transfer unit and if he was to change this to gas or oil he would be getting another benefit too.

“Overall, if he implements the changes here it is going to drop his GHG emissions by a further 9.1% and will increase his profitability by €8,303,” concluded Stuart.