While the Government has committed to investigating the long-term potential of establishing a wide-scale biogas industry in its newly-published Climate Action Plan, the prospects “remain challenging”, according to the Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Michael Creed.

A total of 34 actions for agriculture are outlined in the plan – largely based on Teagasc’s Greenhouse Gas Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (aka ‘MACC Curve’ or ‘Teagasc Climate Roadmap’) – aimed at achieving a target of a 10-15% emissions reduction in the sector by 2030.

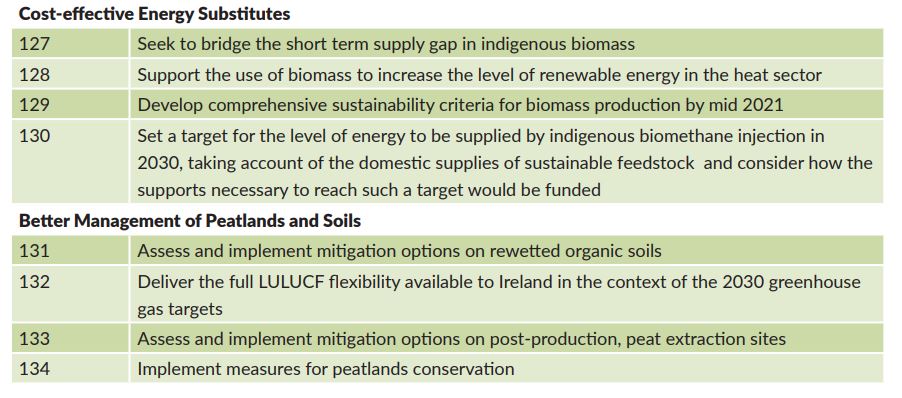

- Seek to bridge the short-term supply gap in indigenous biomass;

- Support the use of biomass to increase the level of renewable energy in the heat sector;

- Develop comprehensive sustainability criteria for biomass production by mid 2021;

- Set a target for the level of energy to be supplied by indigenous biomethane injection in 2030, taking account of the domestic supplies of sustainable feedstock and consider how the supports necessary to reach such a target would be funded.

Speaking to AgriLand after the publication of the plan, Minister Creed acknowledged that the mixing of silage and slurry through on-farm anaerobic digestion (AD) could one day be used to produce biofuel to run Dublin’s bus fleets.

However, he stressed that greater evaluation of the area is needed.

“That is a possibility and there is a commitment to looking at the potential of AD and that will obviously do a cost-benefit analysis on the relative cost of carbon, as opposed to the biomethane that could be produced as an alternative fuel source.

“But, let’s wait and see. There are challenges around it, such as the level of subvention required to support biomethane, and whether that represents the most-effective use of financial resources relative to outcomes achieved in comparison to other things that could be done with that level of subvention,” he said.

With cattle housed for three or four months of the year, the minister cautioned that slurry supplies would be limited.

“It makes sense, there is no doubt. But we are talking about slurry as a feedstock – and slurries here, in contrast with what is happening in AD facilities in other countries, are seasonal.

We don’t have an all-year-round supply of slurry because we have a grassland-based production system, so it becomes a question of what is the level of support required to get other feedstocks into the system – such as silage and beet.

“If you are at the moment leasing lands in parts of the country paying €300/ac, how does that compare to the returns that would be available to use those lands to grow feedstocks for anaerobic digestion?

“Obviously, the way that model works is in the support that is available for the tariff to support the energy generated. There is a commitment in there to investigate this and of course as the price of carbon increases the gap may narrow,” he said.

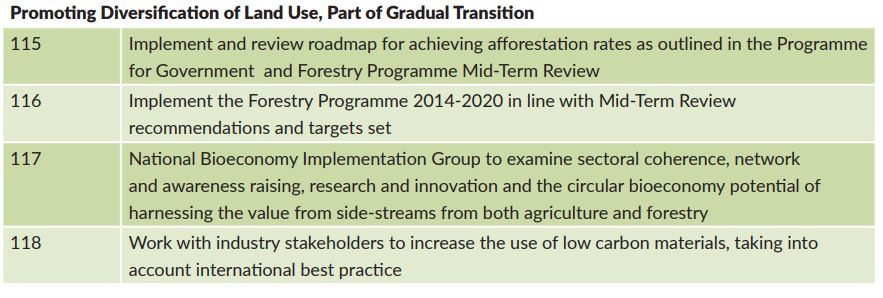

Also Read: How can Irish grassland farmers tap in on a ‘green oil’ boom?In order to meet the required level of emissions reduction over the next decade, a number of abatement actions will be targeted including: an average of 8,000ha of newly-planted forest to be established every year, plus, there will be an active drive to reduce intensive management of grasslands on at least 40,000ha per annum and to improve management on tillage land and non-agricultural wetlands.

A full list of the agricultural actions outlined in the Climate Action Report – which has revived mixed reaction from the country’s farm organisations – is detailed below:

The minister says farmers should not underestimate the significance of these goals; however, he insists the Climate Action Plan is not about pushing a cap on agricultural production – provided the actions are followed.

This is not a cap on production, provided we do the list of prescribed things that are there, there is no fear of a cap on production at all.

“Obviously, if we don’t engage with that other options will have to be looked at.

“I’ve always said in terms of the approach to climate generally it’s like a three-legged stool. It’s being as efficient as we possibly can be in terms of sequestration, which is forestry and displacement of fossil fuels and support for other energy efficiencies, and all that tied into a whole-of-Government approach whereby in 2021 we will be a position to sell locally-generated electricity into the grid from individual holdings for microgeneration.

“But we don’t have to slaughter the herd; we can achieve the objective of a 10% reduction by other measures without capping production.”

Human behaviour

Although the plan does not specifically outline plans to increase the carbon tax, an incremental increase in carbon tax from €20/t to €80/t is expected over the next number of years – in line with budgetary considerations.

Although such a move would lead to stark increases in on farm contracting bills – up €500-€600 per year according to independent TD Michael Fitzmaurice – Minister Creed says it would be “illogical” to ignore such a move in light of recommendations from the Citizens Assembly and the recently-published all-party Oireactas report on climate action.

It would be illogical in the context of the Government approach not to follow though on the recommendations.

“Carbon tax will go from €20/t to €80/t in 2030, and how you do that is a step-by-step increase on an annual basis – that is going to happen.

“A carbon tax is never about raising money, it’s about changing human behaviour in so far as there are alternative options there in terms of renewable energy sources.

“It’s about creating that shift whether you are in urban or rural areas, or whether you are contracting or you are a small business – there are challenges ahead, but there are opportunities as well,” he said.

‘Easy ride’

On the forestry front, the minister intends to write directly to all farmers to engage with them on their concerns.

“It is not a reasonable proposition that we expect any particular corner of the country to take all of the afforestation piece.

“The narrative around forestry is challenging – but it is a critical part of the jigsaw that we need.

“As we generate carbon, which is an inevitable consequence of food production, we need to sequester carbon as well – whether that is through afforestation or appropriate management of peatlands.

Nationally, we need to get 101 million tonnes of carbon out of the system – that’s the journey we are on.

“If you take into account the credits that are given to us for the historical investment we have put into land use, land use changing and forestry – combined with the 10% target and the credits – we are actually contributing as a sector 42% of the distance to the 101 million tonnes.

“This issue of agriculture getting an easy ride here is far from the case. 2030 is just a milestone in a longer journey to a zero-carbon society. It will be normalised into the agenda of farming very quickly,” he said.