In addition to the human misery inflicted on Ukraine by the Russian invasion, the war has led to a huge debate around the fundamentals of EU energy supply and the need for an immediate revamp of overall EU energy policy.

There is additional complexity relating to how this might fit with decarbonisation of the EU economy in response to climate challenges.

While hindsight is a great producer of insights after the fact, the Ukraine war, following the Covid-19 pandemic, Brexit and the recession from 2008 to 2012, in addition to the global climate challenge, points to the need for multifaceted responses to multifaceted challenges.

Moreover the speed with which each crisis has followed the last, means that policy plans and platforms require both depth and flexibility and can in truth have a very short shelf life.

EU attitude to food

In that context, the silence from EU quarters around where the EU Green Deal and EU agri-food policy in general now sits, is quite deafening.

It used to be said that EU policy was the original super tanker equivalent – very slow to change direction or pace; it now seems to be calmed and drifting.

As agriculture moves into the 2020s, there would have been concern in recent years that the key drivers of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform, created a definitive shift towards bilateralism in trade deals.

These key drivers include the 2020 review of the EU response to World Trade Organisation (WTO) pressures dating back to the mid 1990s, to continue to decouple payments from production and to eliminate any and all export subsidies, despite the fact that there has not been a successful multilateral trade deal since Uruguay in 1994 and the stalling of the Doha round in 2008,

While Phil Hogan was EU Trade Commissioner, the economic contribution of the agri-food sector was regularly dialled up.

The ethos of the current disposition of DG Agri, as per Agriculture Commissioner Janusz Wojciechowski, seems to be that moving all farming to a fully organic platform is a silver bullet.

Indeed the narrative behind the EU Green deal and its focus on constraining EU output has elements of a hangover of early 2000’s view that EU agriculture is a ‘sunset’ industry and future food production should migrate to developing countries like Brazil.

Economic contribution of agriculture

This dismissiveness of agriculture as a modern economy factor has now morphed into regular commentary from the commission that constraining agricultural output, and in particular livestock sector output, is a more important action in reducing EU emissions.

More important even than addressing more blatantly fossil fuel-based and scientifically more impactful challenges such as coal mining.

Indeed there is rarely a statement from the commission on climate action that doesn’t highlight the ‘need’ to reduce consumption of meat and dairy products, as if this were again some kind of silver bullet.

Irish agricultural policy

This indifference to the dynamic reality of supply shocks and the basic scientific realities of climate challenges, has been very much compounded in an Irish economy context by the onslaught of the environmental lobby in Ireland that pushes the constraining of Irish food production in its current form, as a key climate policy imperative.

Mature reflection is required.

Clearly and publicly there is ongoing discussion on the need for EU countries to wean themselves off Russian gas and oil and to secure alternative energy supplies.

And while also very publicly, this debate is prioritising the accelerating of alternative renewable energy production, there is complete acceptance of the need for fossil fuel-based energy sources in the short to medium-term.

Quite frankly we need a current debate at EU and Irish national level on future food policy based on well grounded pragmatism and economic and scientific realities.

I believe that such an approach, starting at home, would recognise that while Irish agriculture has committed to deliver its fair share of the Irish economy’s decarbonisation commitments, the constraining of Irish livestock production, as a core value, doesn’t make sense.

Not only is it unwise given the realities of the hyper volatility we now live in and the challenges that this brings regarding access to international food supply chains, constraining Irish agriculture was, and is, hugely detrimental to the real Irish economy.

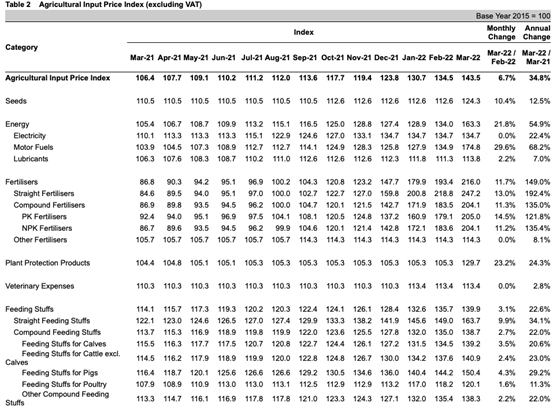

Indeed while there are significant input cost challenges across the agricultural sector in 2022, as set out in the chart from the Central Statistics Office (CSO) above, the increased prices in the beef and dairy output prices in the agricultural output price chart below, will make a huge contribution to the value of Irish agricultural output across the Irish economy in 2022.

The great economist JM Keynes said: “When the facts change, I change my mind, what do you do?”

We need a change of mindset at EU leveL regarding to the new realities of agri-food production and pricing, a good first start to an updated EU debate would be an update here at home.