Ireland’s notorious gross domestic product (GDP) figures, which memorably saw a 25% increase in just three months in 2015, are a very unreliable indicator of our economic performance and wellbeing.

In contrast, the publication of the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment’s Annual Business Survey of Economic Impact 2019 is much more accurate in the context of assessing what the real drivers are of Irish-economy jobs, exports and growth.

By measuring spending in the Irish economy across all sectors – payroll, services and, most crucially, raw materials purchased – the survey gives a much clearer picture than the national accounts of actual Irish-economy activity versus that of firms that pay taxes in Ireland, but have a minimal Irish-economy impact.

The most recent annual survey for 2019 was published in April this year.

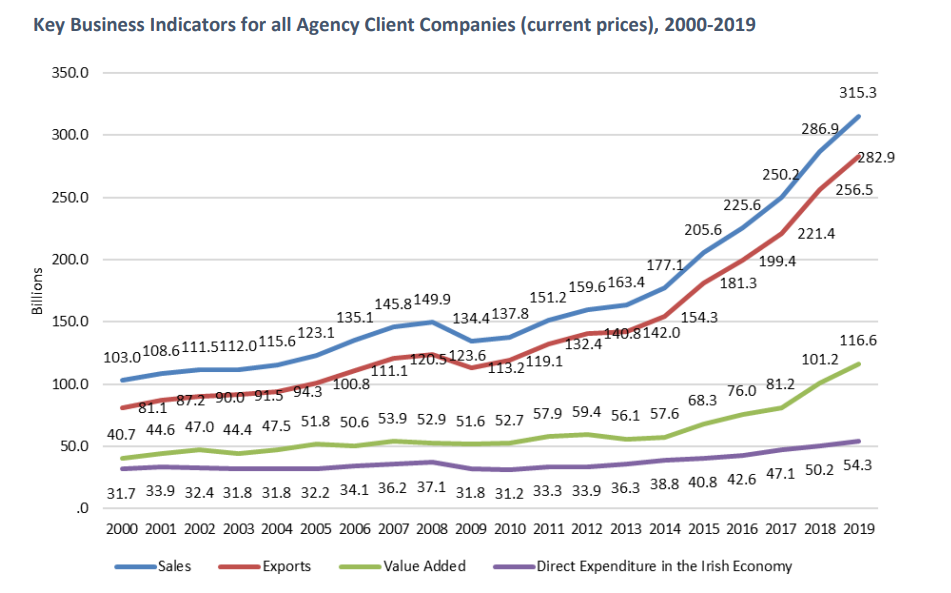

As the chart below shows, if we measure economic performance solely in terms of exports (blue line), sales (red line) and value added, we get a hugely exaggerated profile versus the reality indicated by Irish-economy expenditure (purple line).

So, while multinational sales and exports are €290-€315 billion, almost 20 times as much as indigenous companies, multinational spending in the Irish economy – which is the true measure of Irish economy impact – is €27 billion (versus €26.9 billion from the indigenous sector as the table below shows).

By focusing on Irish-economy impact only, we get a picture of the impact of each sector on the Irish economy rather than their export/sales figures (or the GDP figures versus the global impact of multinational businesses).

A further examination of the government survey shows that the agri-food sector, on its own, provides almost one third of all industry Irish-economy expenditure at €17 billion annually.

This is three times the next largest sector – pharma – at just under €5 billion.

The takeaway from this government analysis is very clear: the agri-food sector is not only a key driver of Irish economy activity, but is actually the biggest driver of Irish economy activity.

This reality must be a key factor in addressing Ireland’s post-Covid-19 economic recovery, as Ireland faces significant challenges (above and beyond the broad recovery) in global-economy performance that will, hopefully, see a rise in all economic activity.

Clearly, proposals by the G7 and, indeed, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to reform global corporation taxes, and introduce a new minimum of 15%, could mean a significant change in our inward investment performance if US companies, in particular, were to favour more tax and economic activity in the US than before.

There has been a lot of commentary in mainstream media recently regarding the broad consensus that very large global companies cannot continue to pay comparatively tiny amounts of corporation tax.

As well as the moral dilemma this raises, the immediate need for all governments to raise taxes to pay for Covid-19 supports and post-pandemic stimulus requires that large global corporates pay their fair share.

Ireland, however, has a somewhat ambivalent position regarding the issue of raising corporation tax.

While it clearly needs to secure tax increases to address government payment commitments, Ireland has, for over 50 years, benefited from a low corporate-tax regime.

Any major changes to this comparative advantage would reduce inward investment and Irish economy activity .

So, on the one hand, we are supportive of the overall moral and economic imperative.

On the other hand, we need the golden goose to continue to lay golden eggs.

But Ireland’s agri-food sector, which is the single biggest sector in terms of Irish economy impact, faces real challenges from Brexit and global-economy impacts.

In addition, it must survive the onslaught of the Irish environmental pillar, which is not only actively suggesting that Ireland should cease and desist the production of meat and dairy products, but is attempting to ensure that the 2021 Climate Action Bill ensures this is so.

How did we get here?

Could I suggest that, in addition to addressing the general ignorance regarding the true economic impact of the agricultural sector, one of the challenges we face involves communicating this positive impact, as well as its very strong future, to a wider audience and leaving behind a lot of the ‘row in the dressing room’ stuff, even if that gets media attention.

The multinational / foreign-direct investment sectors have shown what can be achieved by focusing on a positive image and positive messaging.