Agri-emissions reductions will determine burden on other sectors

As the primary polluter in Ireland, agricultural emissions reductions will determine the burden to be placed on the rest of society, according to Emeritus professor at Maynooth University, and climatologist, John Sweeney.

He was speaking at a recent Joint Oireachtas Committee on Environment and Climate Action (JOCECA) dealing with Ireland's first-ever carbon budgets.

Published in October 2021 by the Climate Change Advisory Council (CCAC), Ireland’s carbon budgets outline our path to achieving a 51% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030. For the agricultural sector, the CCAC has recommended a 22-30% emissions-reduction target.

Professor Sweeney was one of several witnesses providing expert opinion and oversight of the CCAC's proposed carbon budgets, summarised as follows:

The CCAC's proposed five-yearly carbon budgets are consistent with emissions in 2018 of 68.3Mt CO2e reducing to 33.5Mt CO2e in 2030. This equates to the 51% emission-reduction target by 2030.

Addressing the JOCECA, Professor Sweeney highlighted the main problem areas which, he said, are not showing adequate signs of reduction - agriculture and households with transport.

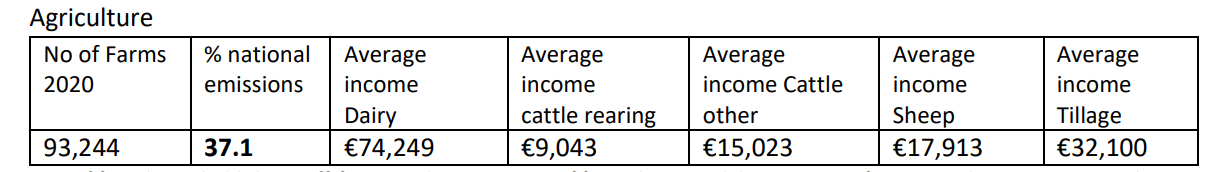

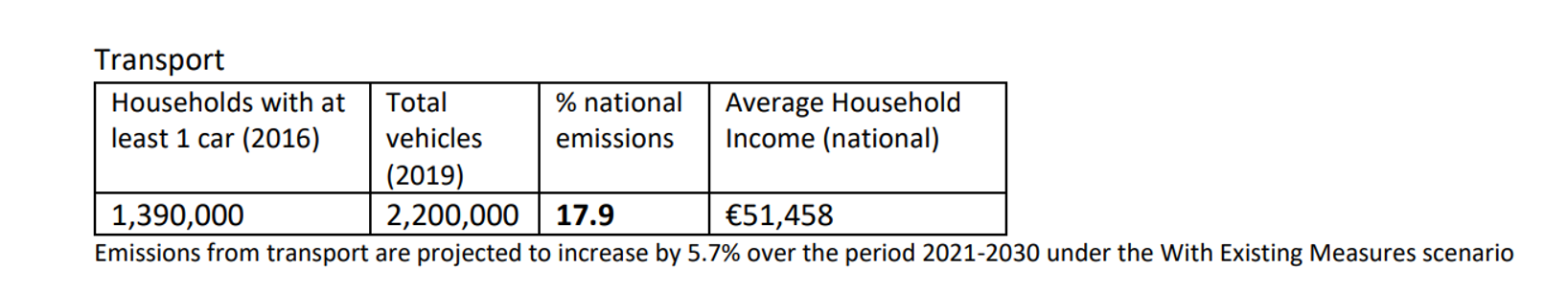

"You can see how our 93,244 farms are responsible for 37% of our emissions and you can see how our 1.39 million households with cars are responsible for almost 18% of our emissions.

"Here are the two sectors we have to address very effectively to make the carbon budgets viable and credible at a national level," he said.

In relation to residential, energy and manufacturing sectors, he credited the energy sector as the success story that" will continue to be the baseline from which we draw most progress in the next few years".

Allocation of sectoral budgets

If our overall carbon budgets are to be credible, it requires commitment and credibility at a sectoral level also, he said.

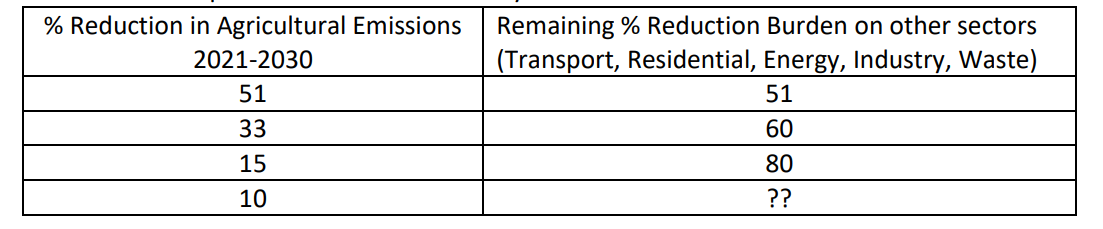

"If we go for a 33% reduction in agricultural emissions, it means that the rest of society - those millions of households, for example - will be expected to pay a heavier burden of around a 60% reduction.

"That is quite a considerable reduction to anticipate over the next 10 years.

"And if we go down to 10%, which is similar to what we are seeing in some of the Food Vision documents, the burden becomes very heavy and impractical for the rest of society."

Methane reduction

In relation to Ireland's commitment to the proposed 30% reduction in global methane emissions by 2030, Prof. Sweeney commented that this is important and relative to the credibility of our carbon budgets.

Ireland has not yet determined how it will contribute to achieving this reduction, he said, adding: "Let's wonder why. Do we really expect the rest of the world to carry our burden once again?

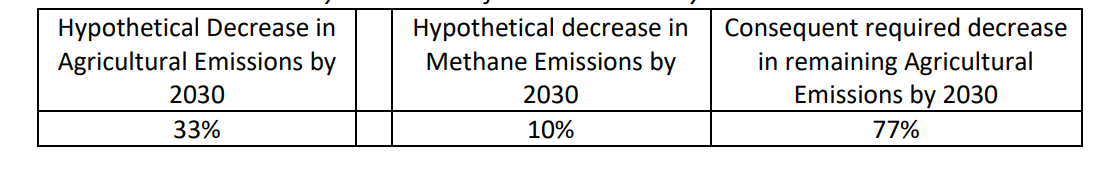

"If we were to reduce our agricultural emissions by 33%, for example, and, if as part of that, we were to reduce our methane emissions only by 10% - and that is a figure which corresponds to what is being offered in Food Vision 2030 - then the reality is that the rest of agriculture would have to face a 77% reduction.

" So, there are intra-sectoral issues and intra-sectoral divisions of just transition which are huge if we are not willing to bit the bullet on a large scale.

Prof. Sweeney said that he had major concerns about the success of the carbon budgets due to slippage and timing issues, described by him as the "deathbed of many climate policies over the years".

The first five-year targets must be adhered to strictly for the second five-year targets to be achieved, he said.

But these are not just targets, he explained:

"These are legally required limit values and if we are not meeting them by the end of 2022 and even early in 2023, we will be required to make savage reductions in sectors to achieve them by 2025. Make no mistake about that."

He also said Ireland must improve on its nitrogen consumption and fossil-fuel subsidies.