Where will the next generation of bulls will come from?

Dr. Donagh Berry recently discussed the success of the Economic Breeding Index (EBI) as it celebrates its 25th year in operation, before going on to question what else needs to be improved in Irish breeding.

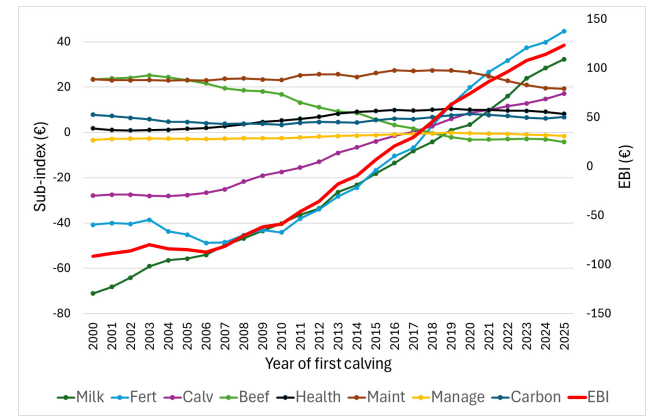

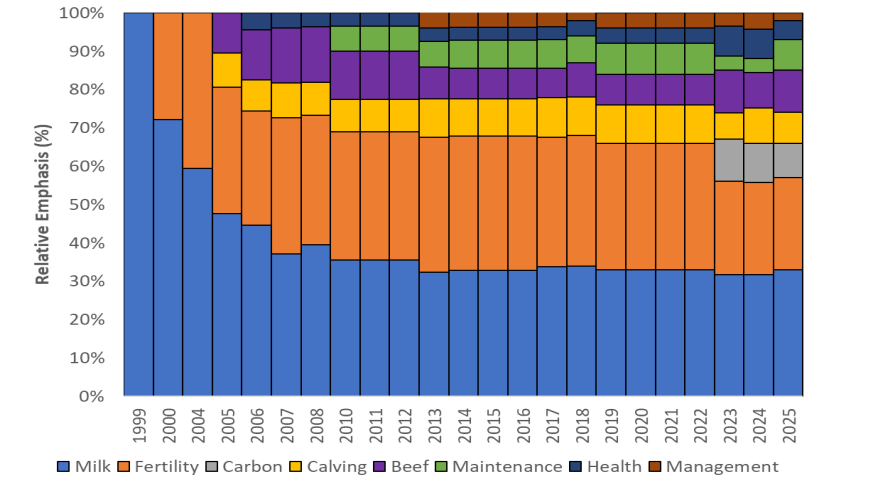

The EBI was first introduced in 2001, replacing the Relative Breeding Index, and has since undergone several changes to stay up to date with the national herd, with the latest base change coming into play back in September.

Dr. Berry, who is a senior principal research officer and quantitative geneticist with Teagasc, referred to the EBI as a 'free tool' that has pumped an estimated €5.4 billion into the dairy industry through improved genetics over the last 25 years.

These improved genetics are evident, considering the EBI of the national dairy herd has risen by €191 since being introduced, making each cow approximately €350 more profitable per lactation.

Berry took a 'walk down memory lane' at the National Dairy Conference last week to review the success of the EBI and explain the need for constant changes.

The quantitative geneticist said: "The key thing about breeding is that bull or calf born on your farm next year and picked up by an AI station, their genes are really not going to be expressed for another seven to ten years.

"So as breeders, we always need to be ahead of the game."

This is done through updates like the recent base change, or 2007 changes to the EBI ahead of the abolishment of milk quotas.

A more recent and controversial change was the deployment of the carbon index in 2023, which a lot of people were unhappy with.

However, Berry explained how this incorporation acts as an 'insurance measure' in case carbon tax is introduced in Ireland.

This highlighted the fact that the dairy industry is constantly changing, meaning updates to Irish breeding are necessary in an attempt to 'stay ahead of the game'.

He said that Irish farmers will realistically see health become the new fertility over the next few years in terms of importance, as improvements in technology such as collars are leading to ageing herds and additional data.

Improvements

Dr. Berry said: "Year on year, we are seeing an improvement on fat and protein yields by approximately 50kg.

"My biggest worry is where our next generation is coming from."

This is what Dr. Berry followed with, and not in terms of generational renewal, in terms of herds of bulls.

He made the daring point that potentially, in 10 year's time, farmers will not be able to find bulls better than their top cows to breed with.

Genetic gain is predicated on elite females being mated with good bulls to produce a small number of hybrid vigour calves.

However, with the top percentage of the dairy herd now being served with sexed semen to produce high EBI dairy heifer calves to be used as replacements, the supply of these elite high quality dairy bulls is dropping and ultimately starting to put pressure on AI stations.

He said "We need a collective solution for this."

Dr. Berry asked farmers how much would they need to breed their highest EBI cow with a mediocre bull that is not in the top bull list (to avoid inbreeding), for it to have a chance of having a male calf that 'may' be picked up by an AI station.

If this is not done, ultimately the breeding pool will get smaller, which in turn will present a higher risk of inbreeding within the industry.

At the end of the day, a proportion of dairy farmers with the top 1% of cows in Ireland will need to begin breeding dairy cows for high EBI bulls.