TB: Failed roadmaps, new action plan and farmers in despair - what's next?

Seven years ago the Irish government, led in 2018 by Leo Varadkar, set a target to eradicate bovine TB "by 2030".

The then Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Michael Creed, warned at the time that there were "no easy options" for dealing with TB.

But he promised in 2019 that a new "roadmap" would be developed to drive down TB levels "protecting cattle from infection and protecting farmers and farm families from the stress and difficulty of a TB breakdown".

Fast forward to 2025 and to a fresh promise from the current Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Martin Heydon, that he will publish a new "action plan" to tackle the "impact of bovine TB on farm families and to reduce herd incidence and spread of the disease".

In the fifth instalment of Agriland’s new series, Silent spread – Ireland’s TB battle, we look at why Creed's roadmap failed and why the herd incidence rate soared from 4.38% in 2020 to 6.40% by June of this year.

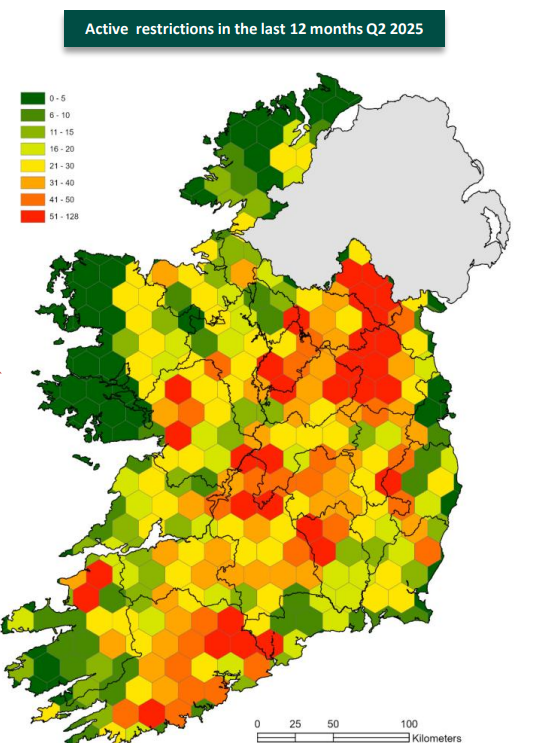

Latest TB statistics show TB reactor numbers hit a high of 43,290 by June and the number of herds restricted between June 2024 to June of this year had also increased to 6,449.

Minister Heydon has repeatedly acknowledged that TB "is having an impact on farmers and their families both financially and emotionally throughout rural Ireland".

No where more so than for farmers in County Cork, where earlier this year there were more reactors identified over a 12 month rolling average compared to any other county.

Behind all of the statistics however are the devastated families, who when their herd comes down with TB, can only watch in tears when inevitably the lorries leave their yards with their livelihood on board.

But why have TB levels soared, to what has been described by the Sinn Féin spokesperson on Agriculture, Martin Kenny, to a "crisis point across the country”?

According to Conor O’Mahony, principal officer with the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) data analysis points to a number reasons for this increase in Ireland including "the expansion of the dairy herd" which has led to increased levels of intensive cattle farming, and the increased movement of cattle.

O'Mahony has also highlighted that some of the other factors that have contributed to the significant TB spread include "the movement of cattle with undetected infection; residual or leftover infection in cattle previously exposed to TB; the inherent limitations of (TB) tests; a reservoir of disease in a protected species, namely the badger; and inadequate biosecurity practices".

TB action plan

The question that must now be answered by Minister Heydon and his officials in DAFM is can TB be stopped in its path in Ireland?

According to the minister he believes there are "five key pillars to address the current rates of bovine TB" which include:

- Supporting herds free of TB to remain free;

- Reducing the impact of wildlife on the spread of TB;

- Detecting and eliminating TB infection as early as possible in herds with a TB breakdown and to avoid a future breakdown;

- Helping farmers improve all areas of on farm biosecurity;

- Reducing the impact of known high risk animals in spreading TB.

Minister Heydon has pledged to "ensure that any measures adopted are based on the best scientific and veterinary advice" but as yet there are no firm details on what his "action plan" will entail or how much money the government will put behind the plan.

But is there any other silver bullet that could solve Ireland's TB problem?

According to DAFM officials "modelling suggests that a vaccine would be the single biggest thing that would eradicate TB".

But that is currently not an option.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) in the UK is currently developing a TB vaccine for cattle and DAFM is monitoring this "very closely".

According to Defra the "candidate vaccine is BCG" (Bacille Calmette-Guérin) Danish strain trialled in cattle under the name CattleBCG.

BCG is the same vaccine used to protect people and badgers from TB.

Vaccine

Defra has highlighted that a number of studies conducted in the past 25 years - where vaccinated and unvaccinated animals were exposed to a stringent experimental infection with the bovine TB bacterium (Mycobacterium bovis or ‘M. bovis’), provide "significant evidence that CattleBCG can reduce the severity of disease in cattle".

However the candidate vaccine cannot be used now because, according to Defra, BCG vaccination "sensitises cattle to the tuberculin tests" - this makes it impossible to distinguish between an animal that is truly infected and one that has been vaccinated.

Most cattle, approximately 80%, react to the tuberculin test- which makes them become false positive animals.

However a DIVA (differentiating infected from vaccinated animals) skin test has been developed to distinguish between infected and vaccinated animals, which will remove the problem of BCG vaccine-related false positives.

This test now needs to be successfully validated and approved for use.

Field trials of the CattleBCG vaccine and the accompanying DIVA skin test began in June 2021 with the next phase due to start in the next few months.

A Defra spokesperson told Agriland that its aim is to "deliver an effective cattle TB vaccination strategy within the next few years".

"We are continuing to work at pace but will only deploy the vaccine and companion DIVA skin test when we have all the right steps in place," the spokesperson added.

Vitamin D

In the meantime the results of a North South partnership study, funded by DAFM, has revealed that vitamin D could have a role to play in influencing livestock immunity to diseases like TB.

The study was the first of its kind as researchers investigated the host immune response in cattle from herds experiencing recurring TB infection.

Three research teams, led by Dr. Kieran Meade in University College Dublin (UCD), in collaboration with Dr. Tom Ford at the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) and Professor Ilias Kyriazakis from the Institute for Global Food Security at Queen's University Belfast examined how "circulating vitamin D concentrations may influence the immune response and outcome of disease on farms which experience bTB relapses".

Professor Kyriazakis, who has a background in veterinary medicine, told Agriland that Queen's University had previously associated the Vitamin D status of livestock with their immune response to a variety of pathogens.

The partnership study investigated the association between circulating vitamin D concentration, TB vaccination, and Mycobacterium bovis infection outcomes in 24 dairy calves, who were less than eight weeks old that were housed throughout and fed a BW-based allowance.

All animals were "infected with 7,600 cfu of M. bovis 52 week post-vaccination, and lung and lymph node tissues were assessed for pathology following euthanasia after week 65".

The results of the study published last year support "an impactful role" for Vitamin D in the development of effective immunity of cattle against M. bovis.

"Gaining insight into the interaction between TB vaccination, M. bovis infection, and vitamin D could potentially guide the optimisation of vaccination protocols and future TB control strategies," researchers found.

Professor Kyriazakis said his work has shown that the content of vitamin D in grass varies throughout the year - especially during the winter when the vitamin D content is low and "below the requirements of the animals".

He said the study showed that was a "negative relationship between vitamin D and pathological lesions and that "higher vitamin D concentrations had lower pathology scores".

"The conclusion is that we really need to take into account how we feed animals in relation to Vitamin D. The level of nutrition affects how animals cope with disease.

"However we do not know how much we should be feeding the animals when it comes to the immune properties of vitamin D," Professor Kyriazakis added,