By Eddie Phelan, southwest regional sales manager, Alltech Ireland

As silage pits begin to open, it is clear that the dry harvest season has had an effect on silage quality. The presence of mould is being reported across the country as overheating occurs in some pits that were harvested at very high levels of dry matter.

To date, the vast majority of silage crops that have been tested are closer to 30% dry matter and above, as opposed to the traditional 25–27% dry matter. Higher dry matter silage is much more difficult to manage; it isn’t as stable, which means pH, sugars and ammonia are promoting both visible and invisible mould growth within the pit.

Additionally, poor pit face management allows air to enter the pit, thus multiplying the risk of mould growth and mycotoxin contamination.

Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are natural substances produced by moulds. They are a chemical by-product used as a defence mechanism by fungi.

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites to moulds. This means they are not produced by the mould all of the time, but most commonly, when the mould is “stressed”, they are produced as a form of defence.

Although stressful conditions that cause the production of mycotoxins are unavoidable in the natural world, it is important that the correct practices are put into place to minimise the risk to livestock as much as possible.

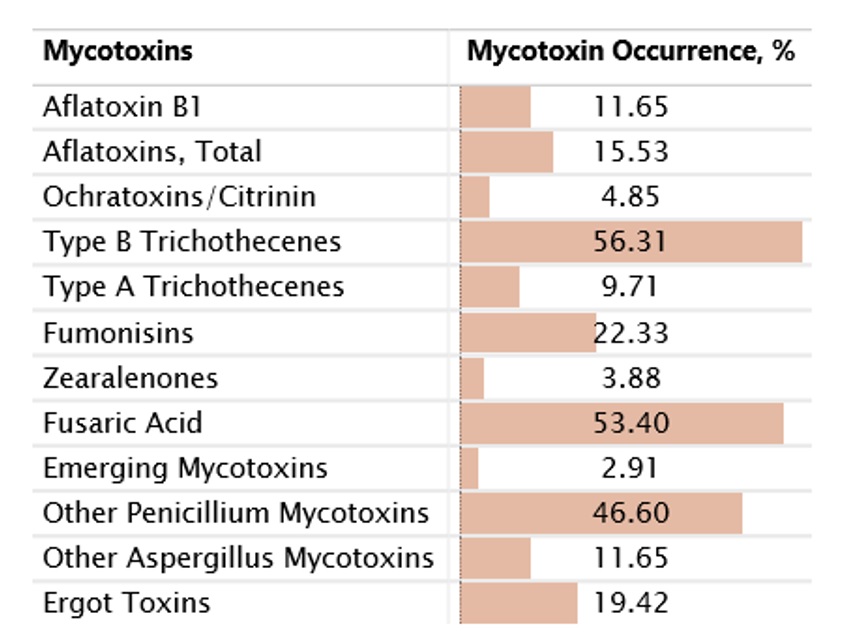

Mould doesn’t have to be present for there to be mycotoxins present. There are around 500 types of mycotoxins, with deoxynivalenol (DON), T-2/HT-2, zearalenone and aflatoxins regarded as the most significant in livestock production.

Mycotoxins are toxic. This means they can negatively affect the health of animals if contaminated feeds are ingested. Symptoms in animals can be varied, but the outcome in all cases includes reduced animal performance.

To put this into perspective, Johanna Fink-Gremmels of the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands advises that “25% of an animal’s genetic potential is stolen by mycotoxins”.

Mycotoxins in Silage

Analysis in Alltech’s mycotoxin lab has shown that mycotoxins are currently being found throughout Ireland. To date, 78% of the 103 Irish forage samples tested in Alltech’s 37+ lab contained mycotoxins, with an average of three mycotoxins present in each sample.

The majority of the mycotoxins found in these samples come from the fungi family and are producing Penicillium and Fusarium moulds. These will hamper natural bacterial activity in the rumen.

The spread and multiplication of these mycotoxins throughout the pit is influenced by silage dry matter and the quality of preservation. Drier forages with a poor level of preservation will rapidly develop moulds.

Risk to livestock

Mycotoxins are often responsible for numerous undiagnosed health issues in livestock – even with reasonably good growing and harvesting practices and pit management.

Ruminants are able, in some capacity, to protect themselves against the harmful effects of mycotoxins. This is due to the strength of certain ruminal microorganisms and their specific detoxifying actions.

In the early stages of infection, mycotoxins such as aflatoxins and trichothecenes act on the immune system, reducing the animal’s immune response. At higher levels, they have an impact on rumen function and the function of other organs (i.e., gut, liver, kidneys), making the animals less responsive to treatments.

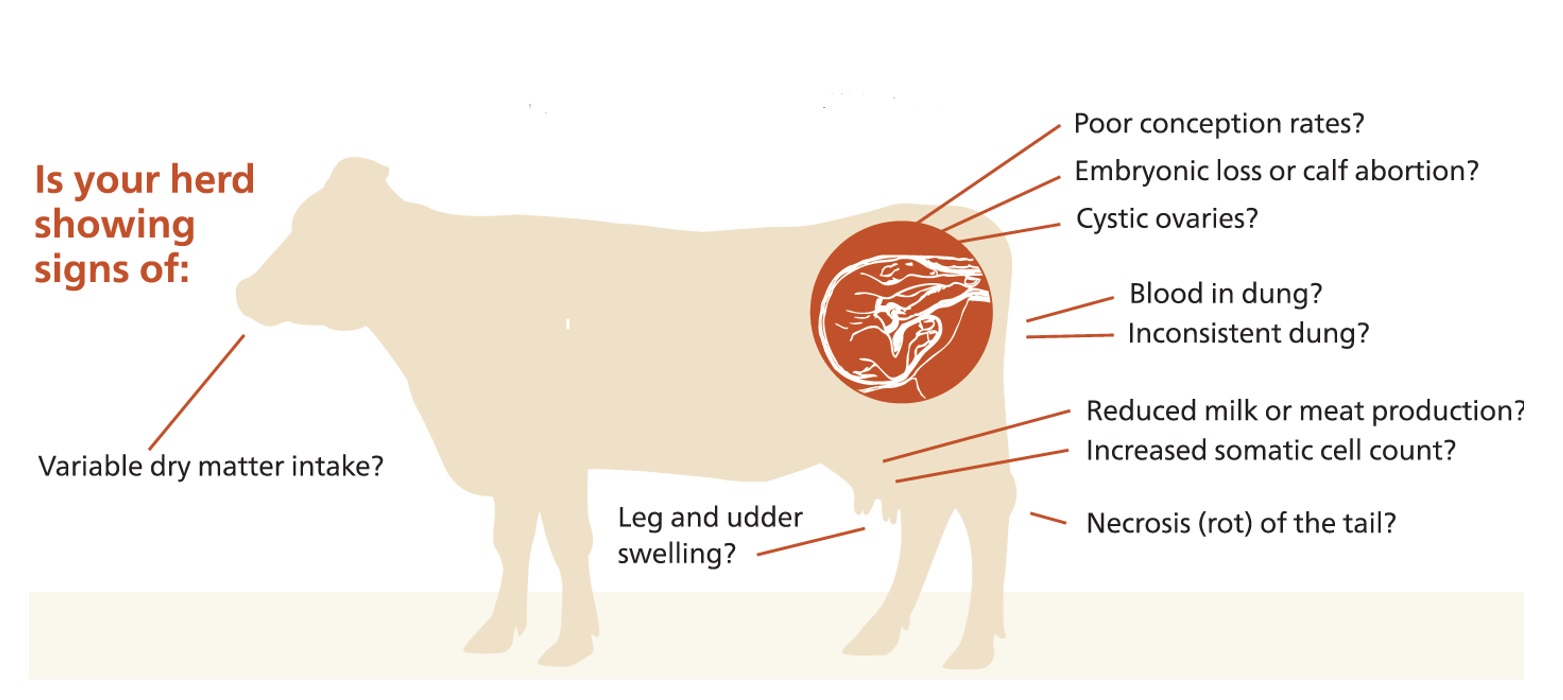

The effects associated with mycotoxicosis in dairy cows can be diverse and difficult to diagnose and include:

- Reduced feed intake;

- Scouring/bloody faeces;

- Reduced milk production;

- Reduced fertility;

- Increased somatic cell count;

- Increased disease susceptibility.

Control and monitor

There are many ways to help control and monitor mycotoxins. No singular method gives full protection on its own, but when some key guidelines are put in place, the risk of mycotoxins can be mitigated.

In the event that the symptoms above are verified as being the result of mycotoxin contamination, the most effective way of dealing with the mycotoxin issue is to eliminate the mould formation and minimise the feeding of affected forages by discarding spoiled feed.

Mycotoxin binders vary greatly, but there are two main types on the market: organic binders and inorganic binders, the latter of which are made from clay and organic binders.

Organic binders will bind more efficiently to a greater range of mycotoxins, reducing mycotoxin absorption without affecting vitamin and mineral counts.

Mycosorb A+® is a broad-spectrum, organic binder based on a specific strain of yeast. It tackles mycotoxins as a whole rather than dealing with individual mycotoxins. Its binding capabilities, broader absorption profile and increased efficacy sets it apart from its competitors.

The effects of adding Mycosorb to the diet can be seen within 24 hours. Mycosorb can be included in feed or through farm pack.

If you think you have an issue with mycotoxins on your farm, contact your local Alltech field representative on: 01-825-2244; or email: [email protected] to discuss implementing a specific mycotoxin program on your farm.

For more information Click here