When it comes to building a house on farmland, there can be a tendency to focus on planning permission – how to get it or how to avoid it – rather than design.

That is the view of Thomas O’Brien, an architect with a practice based between Dublin and Tipperary, that was established in 2011.

“It can be difficult to open up a conversation beyond the obstacle of planning permission,” said O’Brien, who is currently working on a number of rural and urban projects in counties Cavan, Cork, Donegal, Tipperary and Dublin.

“I suspect that the hesitancy toward engaging with the planning system is mainly caused by two compounding problems: a legacy of bad planning and dubious planning decision-making; along with a legacy of incredibly poor construction that fails to comply with planning and building control legislation,” he said.

I cannot speak for all the county councils in the country but, in my own experience, planners follow protocol – and the higher the quality of the design and the detail of the application, the easier they will find it to reach favourable decisions.

“In defence of the planning system, I would contest that many of the applications councils receive are poor, generic, unconsidered documents, providing the minimum of detail and reliant on repeating.

“I mean literally copying the same old tired building types that once worked in the past, but are now without relevance to contemporary legislation, design and sustainability standards,” O’Brien contended.

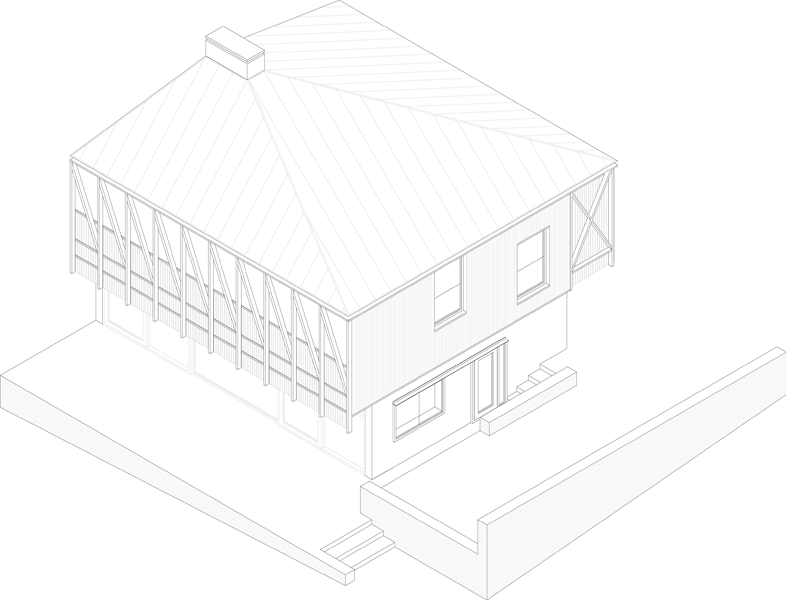

“Every project we undertake is particular, yet builds on a tradition of a critical architecture that evokes aesthetic experience and satisfies the senses.

“For us, each project’s success is measured against its relationship to this tradition. Light and shadow, expert construction and detailing drive the work. We are not overtly looking to be ‘brand new’; our work is referential to history, typology, environmental and contextual prompts,” he said.

“Design adds expense to a project but if you are interested in engaging in a slower, more complex and detailed approach and can bear its obvious cost implications; then working with an architect might be an option worth considering,” O’Brien said.

“Most architects would agree that every construction project is specific, and must be ‘begun again’. The client’s unique location and context, personal requirements and financial constraints, are what steer a project.

The planning process is only a minor part of the longer process of designing and delivering one’s home or place of work. If you are being steered toward hiring a professional whose sole focus is on ‘getting the planning’, I would suggest looking further afield.

“Whether you are hoping to build a farmhouse or a farmyard; if you are interested in architecture, I would advise to take the time to engage a thoughtful practitioner who can offer more than a bald ‘set of plans’.

“If you find yourself in a situation where there is only a little more detail in the drawings that you are building from than the drawings submitted for planning permission, you are not being properly served by your designer,” he said.

“Regardless of how quickly you would like to get building, the process of designing and constructing a quality building is slow.

“By which I mean that the design of a building is a stage-based process where the design is continually augmented and honed over a lengthy period of discussion and negotiation; until you have an incredibly detailed set of drawn and written instruction as to how your building should be constructed just so,” O’Brien said.

Good design is good design whether it is in a rural or urban context. Some architects will be more sensitive to rural contexts or have prior knowledge about farm life and work. But almost any architect would love the opportunity to design a farmhouse or farm infrastructure.

“A decent architect will bring a wealth of experience and insight to each new project but they will also commence a specific project from a position of curiosity, research, and interpretation of that client’s requirements.

‘Most farms are complex’

He said he would not differentiate in this approach whether you are constructing a farm house or the farm itself.

“Most farms in my experience are highly complex spatial arrangements where every object is known, in a pragmatic and an aesthetic sense. One gets on with work on the farm, but is perhaps aware nonetheless of the labour and traditions ingrained in farm life, and how farm buildings are the artifacts of this culture,” O’Brien said.

“When the spatial arrangement of a farmyard is considered it works better, and new farmyards could benefit greatly from some research and reference to successful models and typologies. When a farm is a pleasure to work and pleasing to one’s sensibilities, its longevity is more assured,” O’Brien said.

“With that in mind, one should not feel limited to finding their architect locally. Go online, find images of projects you like, find out who the best architects in the country are, go on their websites, see if you like what they are about.

Give them a call and see if you like them. More information on working with an architect can be found at the website of the Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland: www.RIAI.ie,” he said.